Introduction

Public opinion polls are a crucial part of making sure that democracies work. Understanding the opinions of the public can help guide public policy, help politicians win campaigns, and, as many political scientists note, can help give legitimacy to elections. If polls show a politician losing reelection by 80%, but then they narrowly clinch victory, then voters might call into question whether someone tampered with the results. But if polls show a politician winning, and then do end up winning, then even the opponents of that victorious candidate will have a hard time claiming that the election was rigged. Of course, having good public polling can also help us predict the outcomes of elections ahead of time, so examining past polling trends and then factoring into our predictive models that learned information and current polling data can be useful in making our models more accurate.

Looking at Historical Polling Average Movements

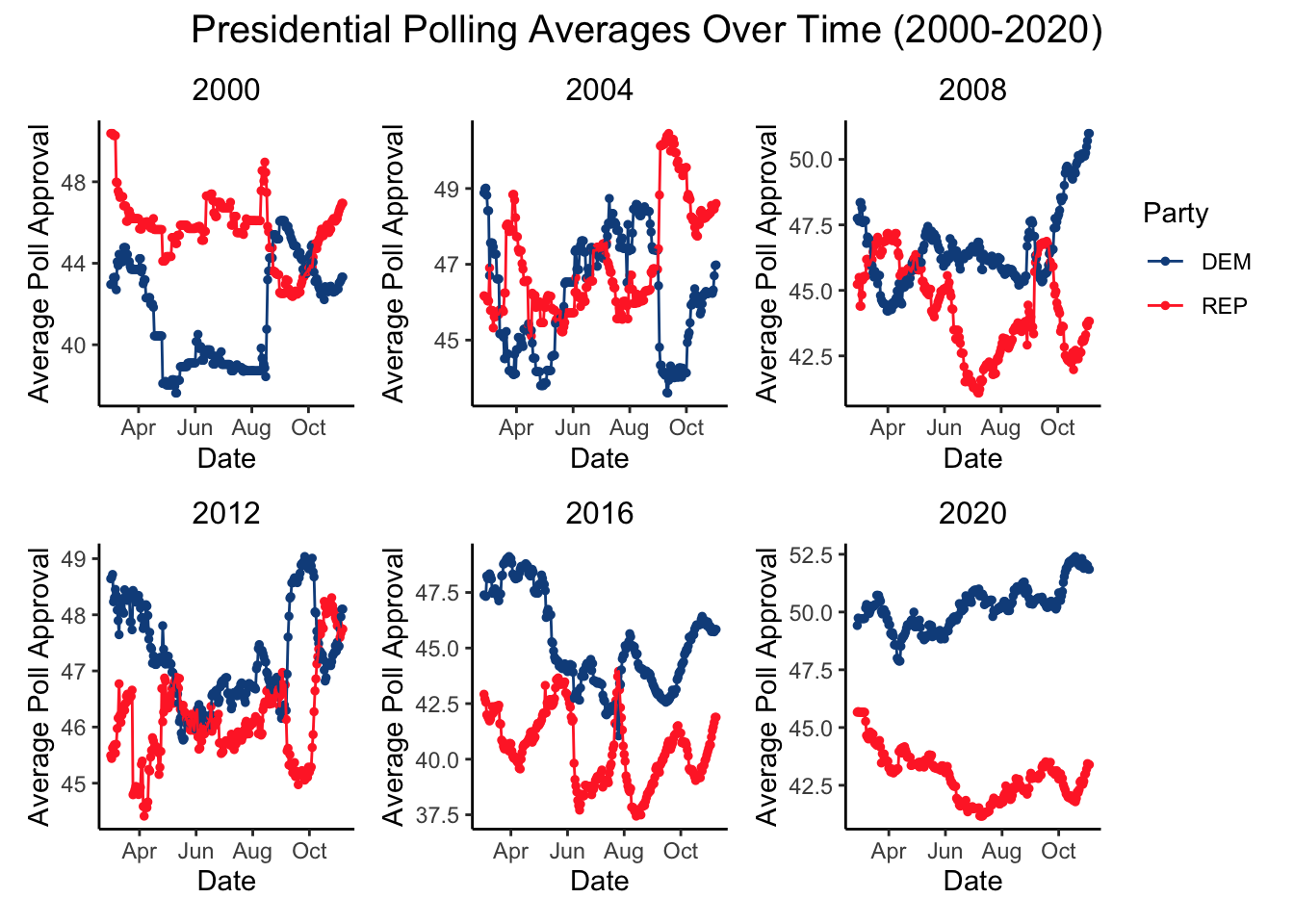

To begin with, I have graphed below the polling averages for the Democratic and Republican presidential nominees between March and November for each presidential election in the 21st century up through 2020.

In each of the six elections, key events during the campaigns can be seen clearly in the corresponding graphs above. For example, in 2000 the RNC and DNC yielded a small bump for Bush but then an even larger surge right afterwards for Al Gore. In 2012, President Obama’s polling numbers cratered following his disastrous performance at the first debate at the start of October, falling beneath Romney’s numbers briefly before ultimately pulling back ahead in the last week or so. In 2016, after gaining on Secretary Clinton throughout most of August and September, Trump’s numbers fell sharply in early October following the release of the Access Hollywood tapes. While, of course, there is no way to officially prove a causal relationship between these “game changer” moments and the temporally corresponding jumps or free falls in polling number, these shifts in poll averages help us understand how the public reacts to key moments in these campaigns.

Looking at 2024

2024 So Far

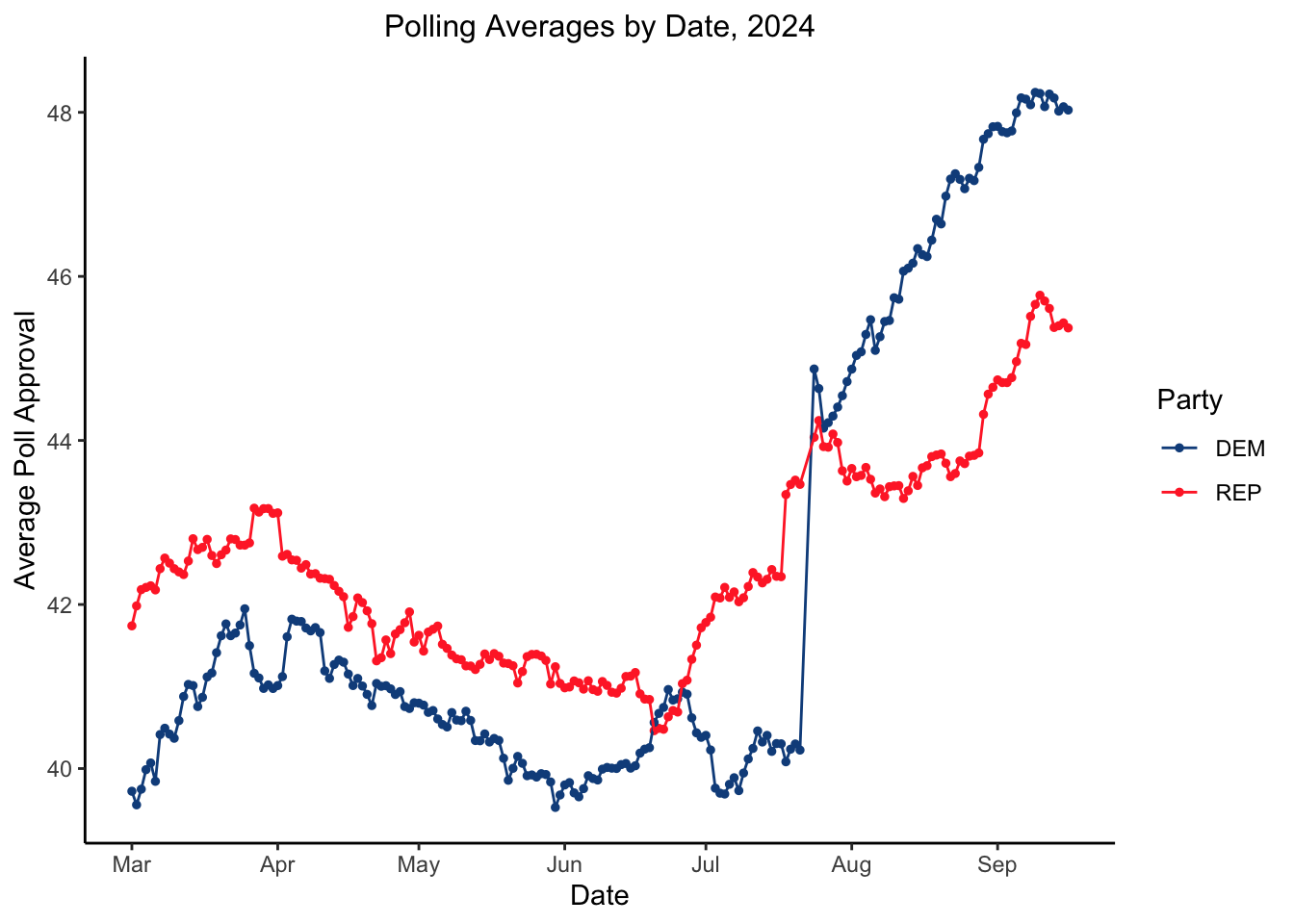

Now looking towards this year’s election in 2024, we can see in the graph below a similar narrative play out.

After narrowly trailing former President Trump in the polls throughout the late spring and summer, President Biden had closed the gap with his opponent by the time the first presidential debate arrived in late June. However, in the two weeks following President Biden’s abysmal performance, Trump’s lead expanded to the largest it had been in the polling average since March. Trump’s numbers then saw a sudden jump following the failed assassination attempt against him and the RNC which immediately followed it. However, shortly after the RNC ended, President Biden announced that he was withdrawing from the race and endorsing Vice President Harris, who immediately surged in the polls as she consolidated support among Democrats. In the following month ad a half, Harris has steadily climbed in the polls, though Trump has slightly narrowed the gap in September. Throughout this month and a half long period following Harris’ entry into the race, she has led Trump by roughly 3-4 points on average.

Modeling 2024 National Two-Party Vote Based off of Polling

Now that we have and can see the polling data so far for 2024, we can compare it to past elections to try to predict where Harris’ numbers will end up on election day. To do this, I will look at the September polling data, since it is the most recent information we have, and use an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression to compare this data with past trends in presidential polling vs presidential election results. Below is the regression table for that relationship between September polling and November election results.

| Democratic Party National Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 23.14 | 0.88 | 21.40 – 24.87 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.56 – 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 420 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.678 / 0.677 | |||

From this, we can see that the slope of the line of best fit is 0.6, which represents a fairly strong positive correlation between poll numbers and election results, and the adjusted R squared value of 0.677 means that a sizable portion of the deviation from the trend line can be explained by the model. We can now use this regression model to predict how Vice President Harris will do in the 2024 election based off of polling averages so far in September.

| Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 51.99 | 37.62 | 66.36 |

For the data I have, I weighted polling data that is closer to election day more than data farther out. The result of this weighted model show Harris winning the two-party popular vote with roughly 51.99%. This said, there is a large range between the upper bound of my model (66.36%) and the lower bound (37.62), so there is not a high level of certainty in this model, however that range would likely decrease notably if I shrunk my confidence interval to 80% instead of 95% as some predictive modelers of elections do.

Modeling 2024 State Two-Party Vote Based off of Polling

This caveat aside, we can apply this same technique to state-level polling, which is important since, as was demonstrated in 2016, Vice President Harris can win the popular vote but if she falls short in the key swing states she will still lose the election. Below is the regression table for the relationship between state-level polling and state-level election results.

| Democratic Party State-Level Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 1.52 | 0.26 | 1.02 – 2.02 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | 1.09 | 0.01 | 1.08 – 1.10 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 8380 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.807 / 0.807 | |||

As can be seen, there is again a strong positive correlation, with an even higher R squared value than the national polling. Applying this model to September state-level polling in 2024 yields the following predictions:

| State | Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 52.52 | 30.33 | 74.72 |

| California | 66.37 | 44.17 | 88.56 |

| Florida | 50.61 | 28.42 | 72.81 |

| Georgia | 53.17 | 30.97 | 75.37 |

| Michigan | 53.41 | 31.21 | 75.60 |

| Minnesota | 55.88 | 33.68 | 78.07 |

| Nevada | 52.77 | 30.57 | 74.96 |

| New Hampshire | 57.07 | 34.87 | 79.27 |

| North Carolina | 52.92 | 30.72 | 75.11 |

| Ohio | 48.20 | 26.01 | 70.40 |

| Pennsylvania | 53.20 | 31.00 | 75.39 |

| Texas | 49.80 | 27.61 | 72.00 |

| Virginia | 55.79 | 33.60 | 77.99 |

| Wisconsin | 54.56 | 32.36 | 76.75 |

Once again, the caveat of high upper and lower bounds to the distributions for each state in this model is important to note. This said, state-level polling seems fairly optimistic for Harris, with this model having her win by over 5-point margins in the two party vote in all seven key swing states, including North Carolina which Trump won in 2020. This model also has Harris narrowly flipping previously Trump-won Florida, and falling just 0.4% behind Trump in Texas. This all said, these models are based off of data that is still a month and a half out from the November election, and the accuracy of polling averages in predicting electoral results gets better as the election draws nearer.