Introduction

Being an incumbent President can theoretically have both electoral advantages and electoral disadvantages. On one hand, incumbent presidents start the race with higher name recognition, they can draw the attention of the media easier given their high profile position, they tend to start with a fundraising advantage, they benefit from voters potentially preferring the so-called “devil they know” to the “devil they don’t,” and they can use so-called “pork barrel” spending to financially benefit crucial voting blogs to try to win over their votes. However, on the other hand, incumbency can prove detrimental in the sense that incumbent presidents can be viewed as responsible for recessions or insufficient responses to natural disasters and they can face potential voter fatigue. Regardless, in recent elections there have been questions of how much incumbency really helps or hurts incumbents given the United States’ increasingly polarized electorate. As such, for my fourth blog post I will explore the issue of incumbency, whether it helps or hurts candidates, and how we might think about incumbency in the unique case of the 2024 election.

Historical Incumbent Advantage

To begin with, let’s take a look at the historical trends of incumbency advantage in presidential elections. The table below shows the proportion of incumbent presidents since World War Two who have ran for reelection and won.

## Elections with At Least One Incumbent Running: 11

## Incumbent Victories: 7

## Percentage: 63.64

As can be seen, of the 11 post-war elections in which the incumbent president ran for reelection, that incumbent won about 64% of the time. The four incumbent presidents who lost were Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush, and Donald Trump. However, when we look at the win rate of the incumbent party, a different narrative emerges.

## reelect_party N Percent

## 1 FALSE 10 55.56

## 2 TRUE 8 44.44

This table shows that, of the 18 post-war presidential elections, the incumbent party has only won 8. As previously shown, 7 of those 8 were times when the incumbent president himself was running, with the 8th case being when George H.W. Bush won following 8 years of being Ronald Reagan’s Vice President. This lends credence both to the theory that voters experience voting fatigue for the incumbent party and to the theory that incumbent presidents have a unique strength to them that is different to a successor candidate.

Pork Barrel Spending Analysis

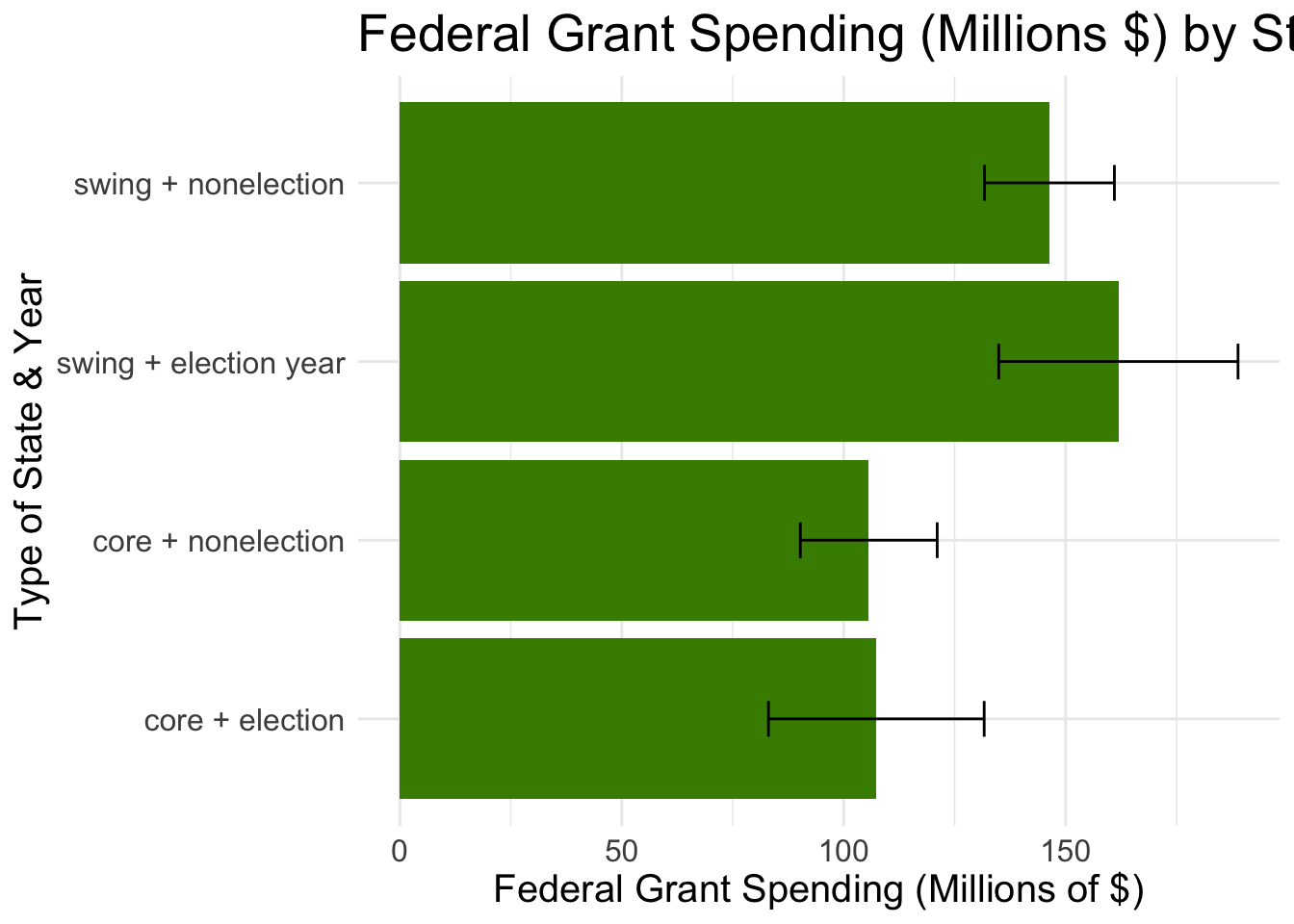

When trying to see why this might be, many observers often point to so-called “pork barrel spending” which is when politicians use their delineated powers to fund (often frivolous) projects in crucial states or constituencies in order to gain the favor of local voters. To examine whether or not this practice of directing additional funds to swing states actually occurs, I have graphed below federal grant spending between 1988 and 2008, seperated by whether that spending was in a swing state or not and whether the grant occured in an election year or not.

As can be seen, there is a statistically significant difference between swing states and non-swing states, with those swing states benefiting from additional grant funding. Interestingly enough, there is not statistically significant difference between grant spending in election years and non-election years. This could be explained by the fact that the projects that these grants fund often take more than a single year to complete, so the community might not see tangible benefits from grant spending within the year, thus yielding little benefit for an incumbent to prioritize grant spending in an election year rather than in the years leading up to it.

This said, just because more grant money is spent in swing states, does not necessarily mean that the incumbent benefits from said pork barrel spending. To test the relationship between grant spending and incumbent vote swing, I ran the following county-level regression. In this multivariate regression I added in variables about other potential factors like whether the county is in a swing state, the percent change in the county’s real disposable income, the difference between the candidates in ad spending, among others.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = dvoteswing_inc ~ dpct_grants * comp_state + as.factor(year) +

## dpc_income + inc_ad_diff + inc_campaign_diff + dhousevote_inc +

## iraq_cas2004 + iraq_cas2008 + dpct_popl, data = d_pork_county)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -27.321 -2.848 -0.025 2.728 22.994

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -6.523210 0.084963 -76.777 < 2e-16 ***

## dpct_grants 0.003954 0.001043 3.792 0.000150 ***

## comp_state 0.155418 0.077223 2.013 0.044173 *

## as.factor(year)1992 -0.156389 0.120591 -1.297 0.194699

## as.factor(year)1996 6.230500 0.119533 52.124 < 2e-16 ***

## as.factor(year)2000 -2.000293 0.118588 -16.868 < 2e-16 ***

## as.factor(year)2004 8.248378 0.119371 69.099 < 2e-16 ***

## as.factor(year)2008 3.574248 0.124060 28.811 < 2e-16 ***

## dpc_income 0.134285 0.022326 6.015 1.84e-09 ***

## inc_ad_diff 0.061345 0.010851 5.654 1.60e-08 ***

## inc_campaign_diff 0.161845 0.013166 12.292 < 2e-16 ***

## dhousevote_inc 0.012093 0.001952 6.196 5.91e-10 ***

## iraq_cas2004 -0.153092 0.069585 -2.200 0.027816 *

## iraq_cas2008 -0.164783 0.021677 -7.602 3.07e-14 ***

## dpct_popl 2.103344 0.530292 3.966 7.33e-05 ***

## dpct_grants:comp_state 0.006411 0.001781 3.600 0.000319 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 4.452 on 17943 degrees of freedom

## (506 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.4199, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4194

## F-statistic: 865.9 on 15 and 17943 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

As can be seen above, a 1% increase in federal grant spending yields a roughly 0.004% increase in the vote share for the incumbent. Although small, this increase is statistically significant. Furthermore, we can see that the effects of federal grant spending on incumbent vote swing is larger in swing states (~0.006%) than in general. This is likely because the increased ad spending and campaign activity in swing states can bring more attention to these grants and the benefits they bring to the community than they might get in non-competitive states.

Incumbency in 2024?

Given the clear impact that incumbency plays in presidential elections, it is worth exploring how incumbency might impact the 2024 election. While the actual incumbent, Joe Biden, has decided not to seek reelection, many have claimed that Trump or Harris could be viewed by some voters as de facto incumbents.

First off there is Trump, whose candidacy is the second time in all of American history and the first time since the 1800’s where a former president has run again. The impact of this unique quality of his campaign is unknown and will be almost impossible to determine, let alone definitively quantify its impact. This view as Trump as a quasi-incumbent has been bolstered by the Harris campaign, who have championed slogans such as “We’re Not Going Back.”

Then there is Harris herself. As the incumbent Vice President, she and her policies are inherently intertwined with the current administration. She was Joe Biden’s preferred successor, and some have claimed that her quick ascension to being the Democratic nominee was a “coronation.” At a time when there is doubt about the strength of the economy, there are numerous foreign policy conflict, and there is dissatisfaction with the Biden administration’s handling of issues such as the border, Republicans have sought to paint Harris as an incumbent worthy of blame attribution.

In my opinion, if one, and only one, of these two candidates were to be counted as the “incumbent,” it would be Vice President Harris. Although Trump is a former president, Harris is the one better able to capitalize on incumbent advantages such as pork barrel spending or the incumbent war chest that Biden had built up which Harris was able to inherit. Harris also faces the potential downsides of incumbency in much more real ways than Trump does. Trump has tried to run much of his campaign by blaming Biden and Harris for inflation and perceived poor economic performance, and voters may feel fatigued by four years of Democratic control of the White House.

Regardless of who is a better fit for the label, it is clear that the incumbency factor in 2024 is no black and white ordeal. Both candidates enjoy some of the benefits and some of the disadvantages of incumbency, and it will be interesting to see how this effects the final stretch of the race, especially as potential “game changers” occur such as Hurricane Helene and the damage it has wrought in North Carolina and, to a lesser extent, Georgia.