Introduction

For this fifth blog post, I want to look at another, likely final, fundamental factor that crucially impacts American elections: demographics. Throughout America’s history, demographic voting divisions have impacted elections, from well-observed racial partisan voting gaps to turnout differences in different age groups to the education divide that helped propel Trump’s 2016 victory to the increasingly emerging partisan gender gap. Because of these issues and other demographics related-trends, campaigns must keep track of what a state or district’s demographics look like. Additionally, although I will not be exploring it in this blog post, demographic changes also are noteworthy to campaigns. For example, the fast-growing, rapidly diversifying Atlanta suburbs will be crucial if Harris wants to win in November, whereas slow-growing or even shrinking rural areas in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania pose a key challenge from the Trump campaign who seeks to rack up votes in those heavily Republican areas. As such, it is important to get a sense of what the demographic makeups are of key states in 2024.

State-Level Demographic Analysis

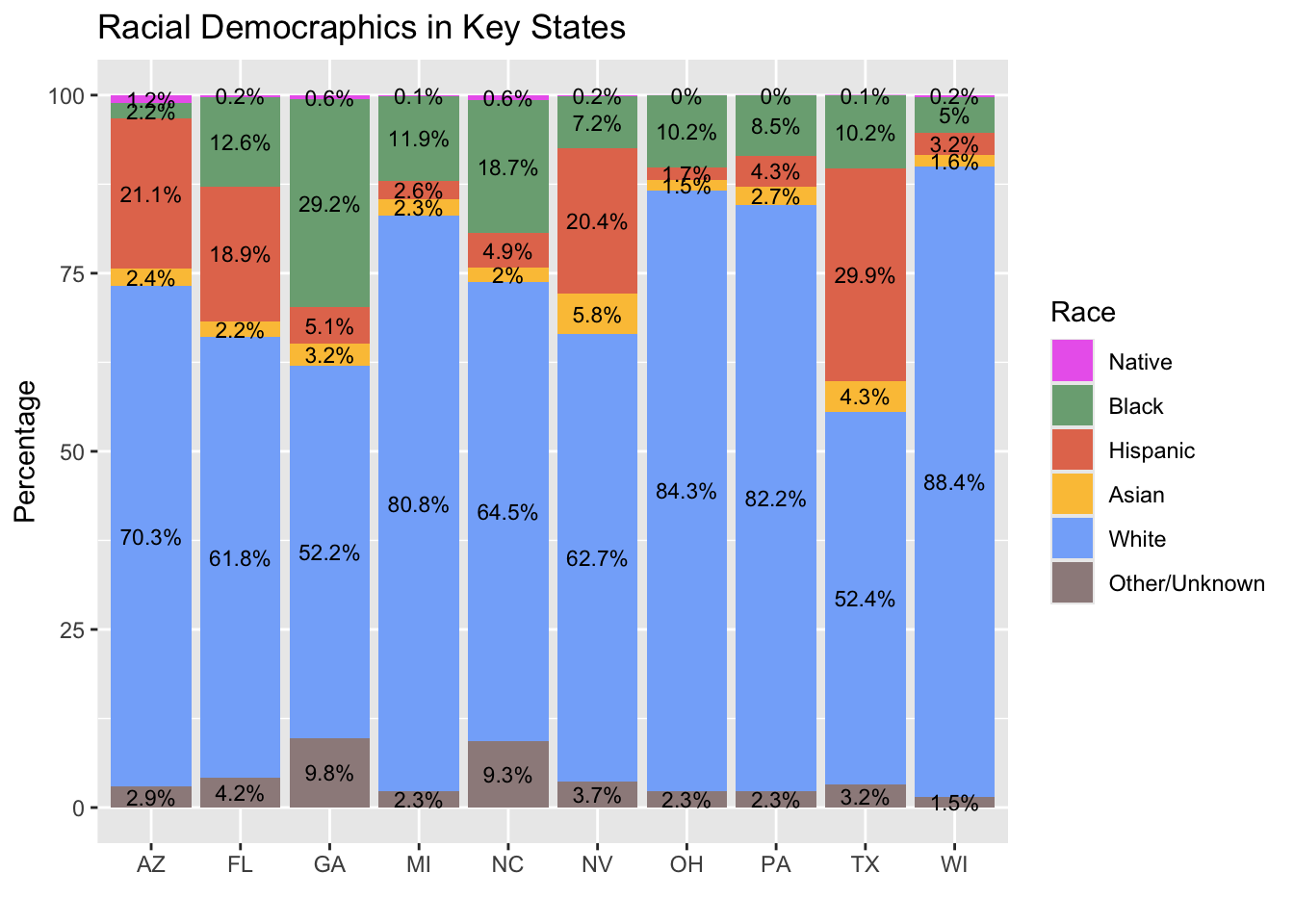

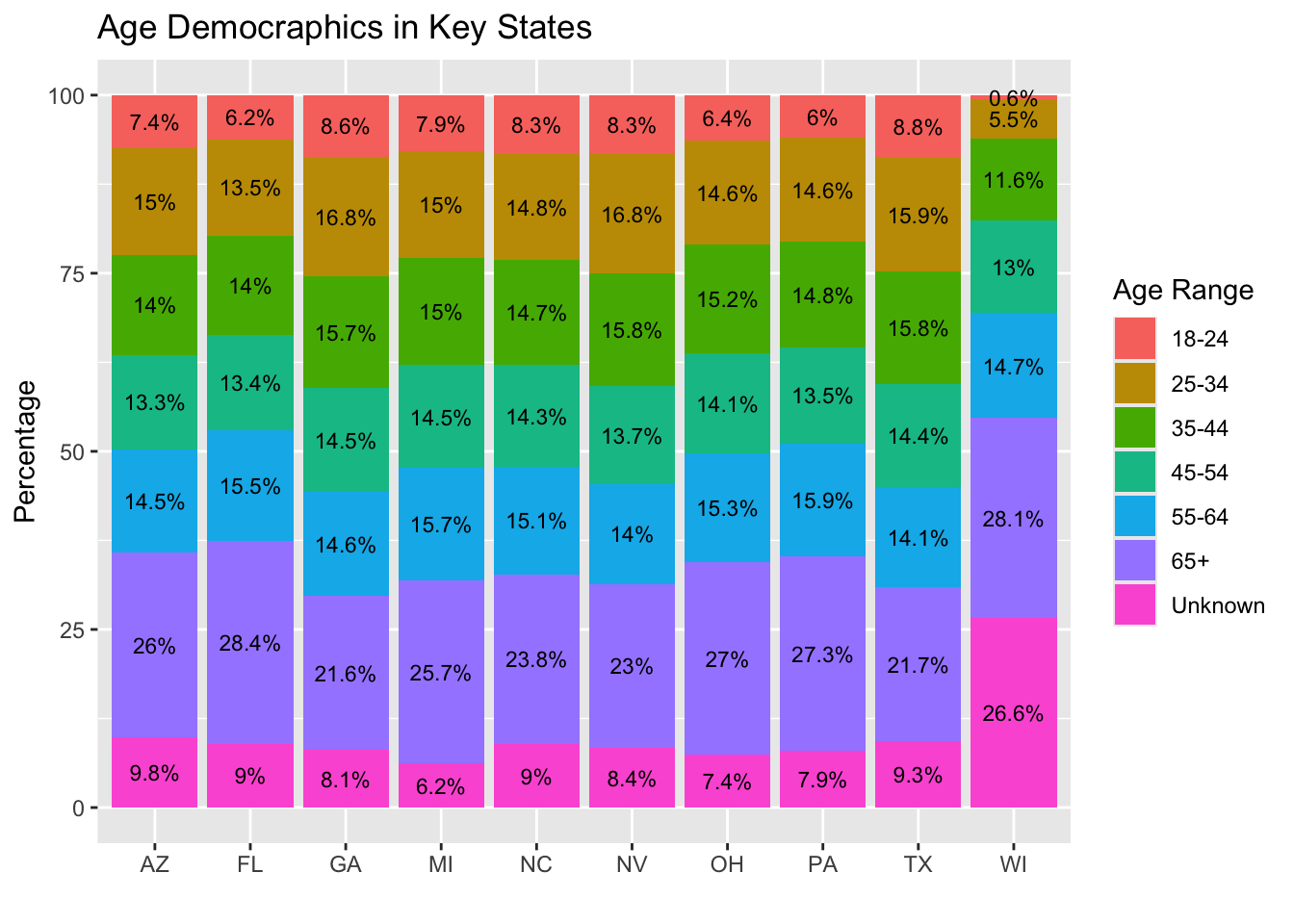

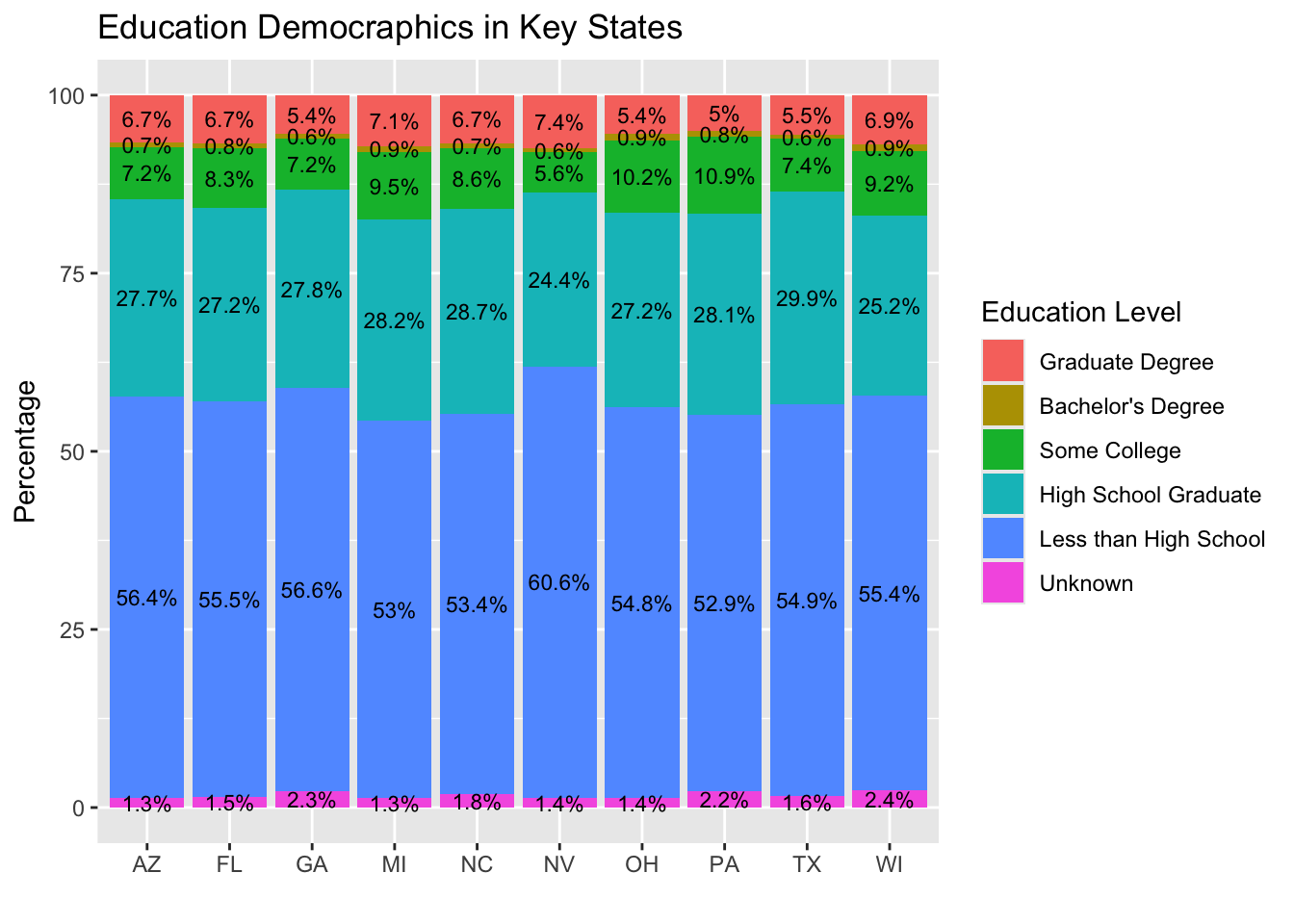

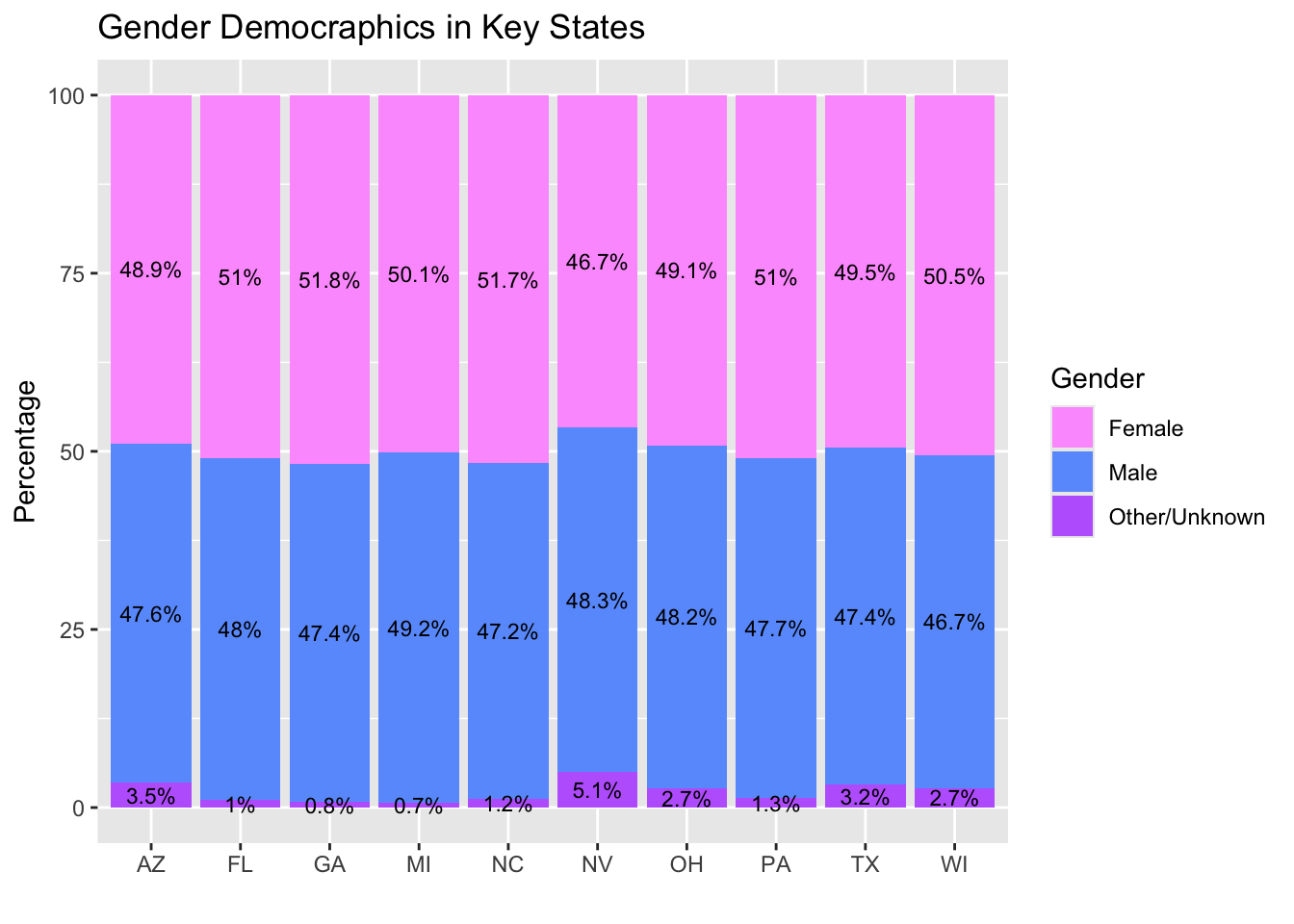

To begin with, I will look at the breakdown of electorates in terms of race, age, education, and gender in the following 10 key states: Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin. To do this, I will use a 1% sample of voterfile data provided by Statara Solutions to visualize and analyze these demographic breakdowns.

The above graphic shows the breakdown of various racial groups in these 10 states. Here, we can see the key differences between the midwest and the sun belt. Over 80% of the voterfile sample in the midwestern states of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were white, showing the importance of white voters, and in particular working class white voters, to winning those states. On the other hand you have the sunbelt, where states either have a high Hispanic population, high Black population, or both.

In terms of the breakdown for age groupings, the clear standout is Wisconsin and their significantly larger “unknown” contingent. This is likely due to either an error or record-keeping practices in the state that seemingly leave the ages of younger registered voters severely under-reported. Putting Wisconsin aside, you can notice certain other differences. For instance, Florida, long a retirement hot-spot, boasts the largest 65+ contingent, while fast-growing Texas and Georgia, and to a lesser extent Nevada, have distributions skewed younger compared to the slow-growing, aging populations in midwestern states like Ohio and Pennsylvania.

In terms of education numbers, the high, unrepresentative proportion of “less than high school” educated registered voters and the all but insignificant count of registered voters with a bachelor’s degree calls into question the accuracy of this data. That said, we can still see some small differences between states, with fairly working class Nevada hosting the largest “less than high school” contingent.

Finally, in terms of gender we can see that each state has a fairly even distribution of men and women.

Turnout by Demographic Group by State

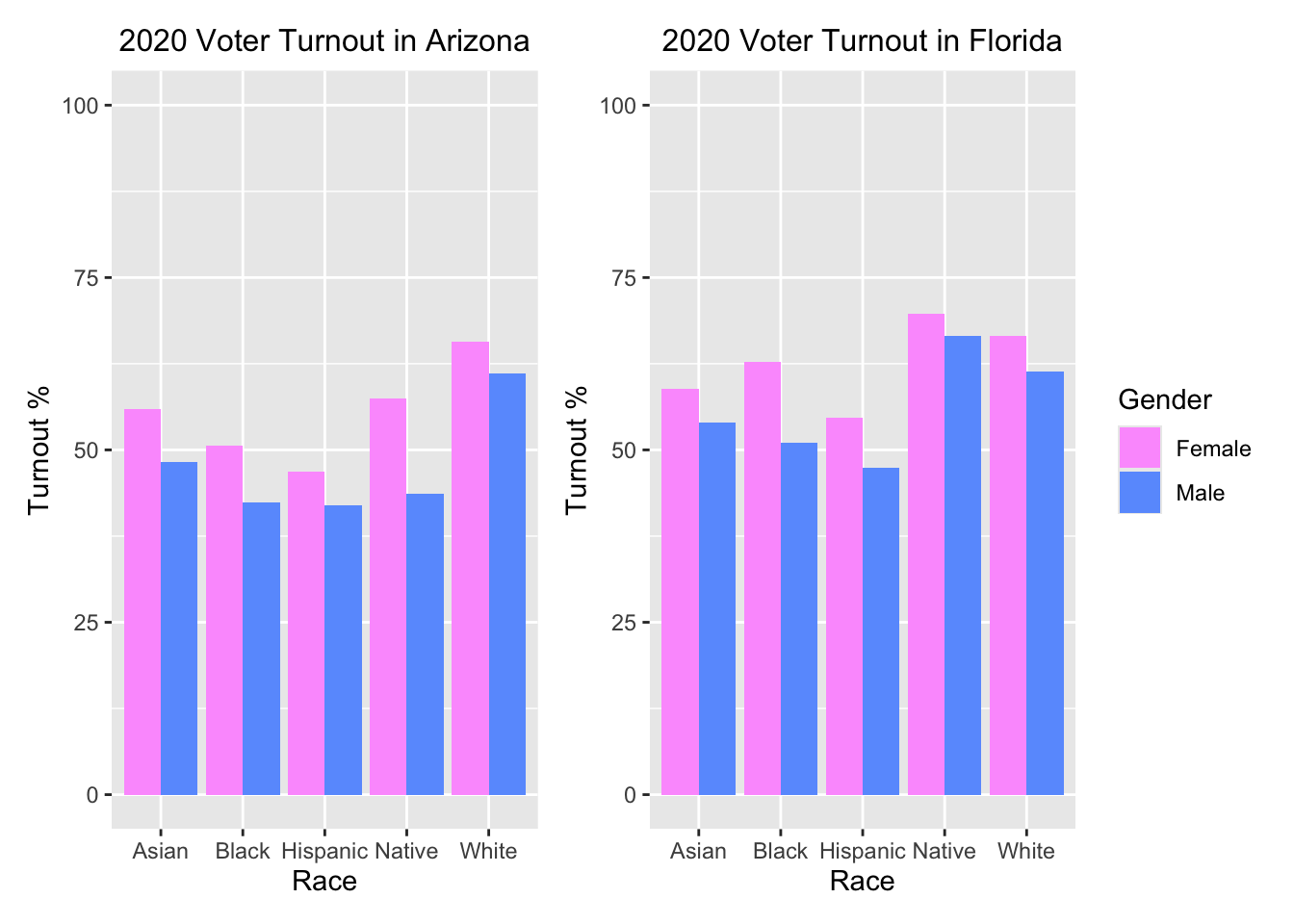

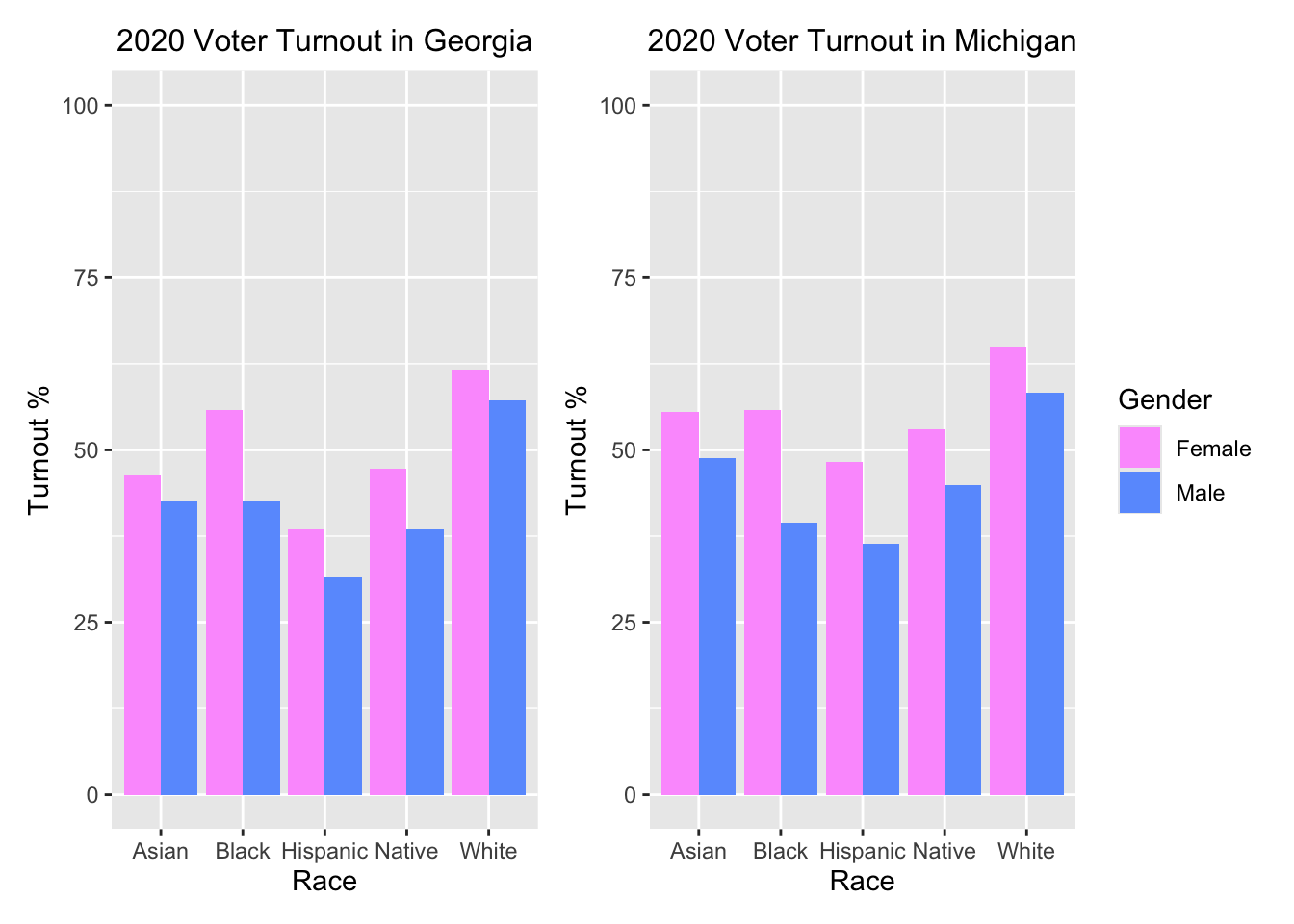

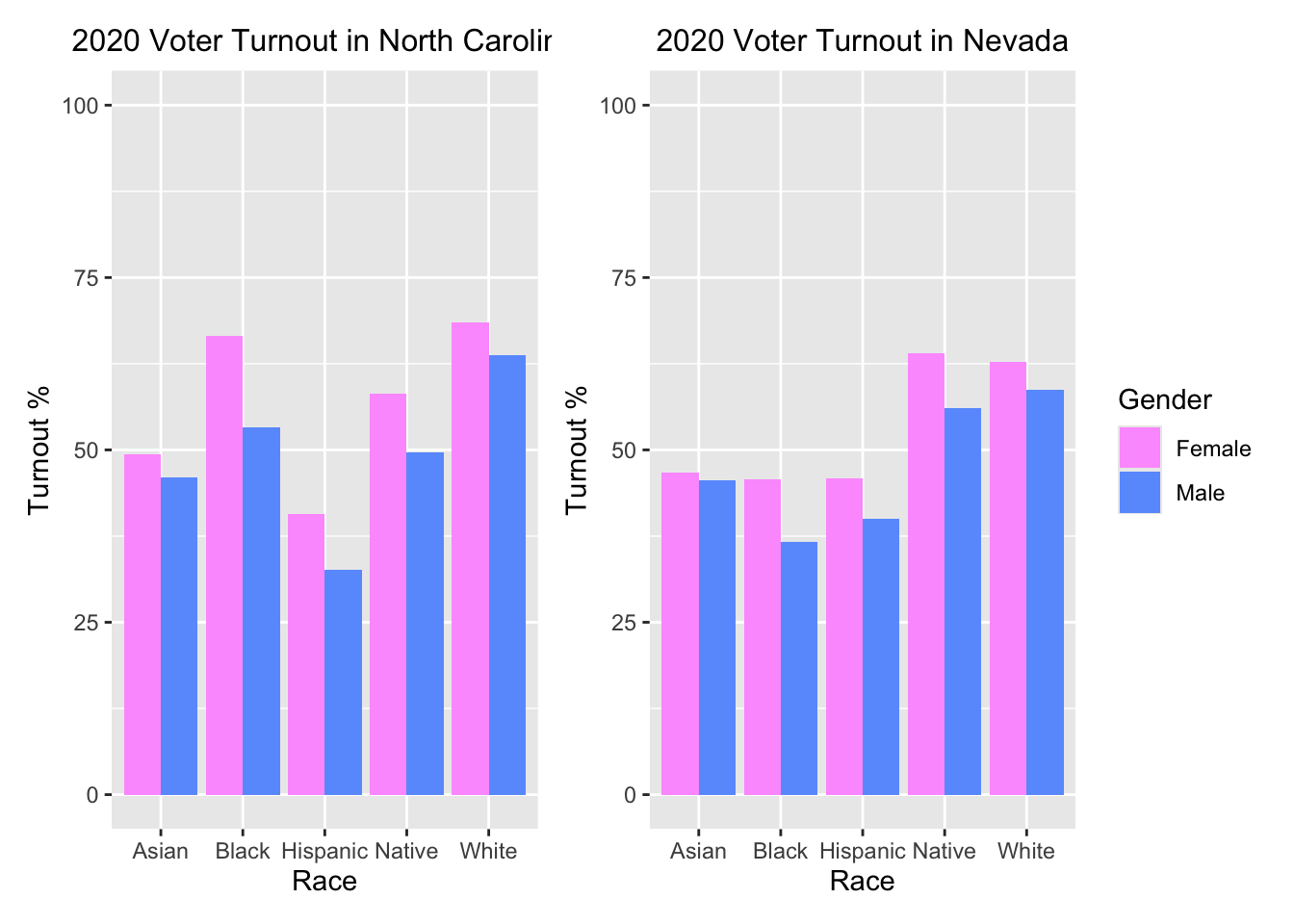

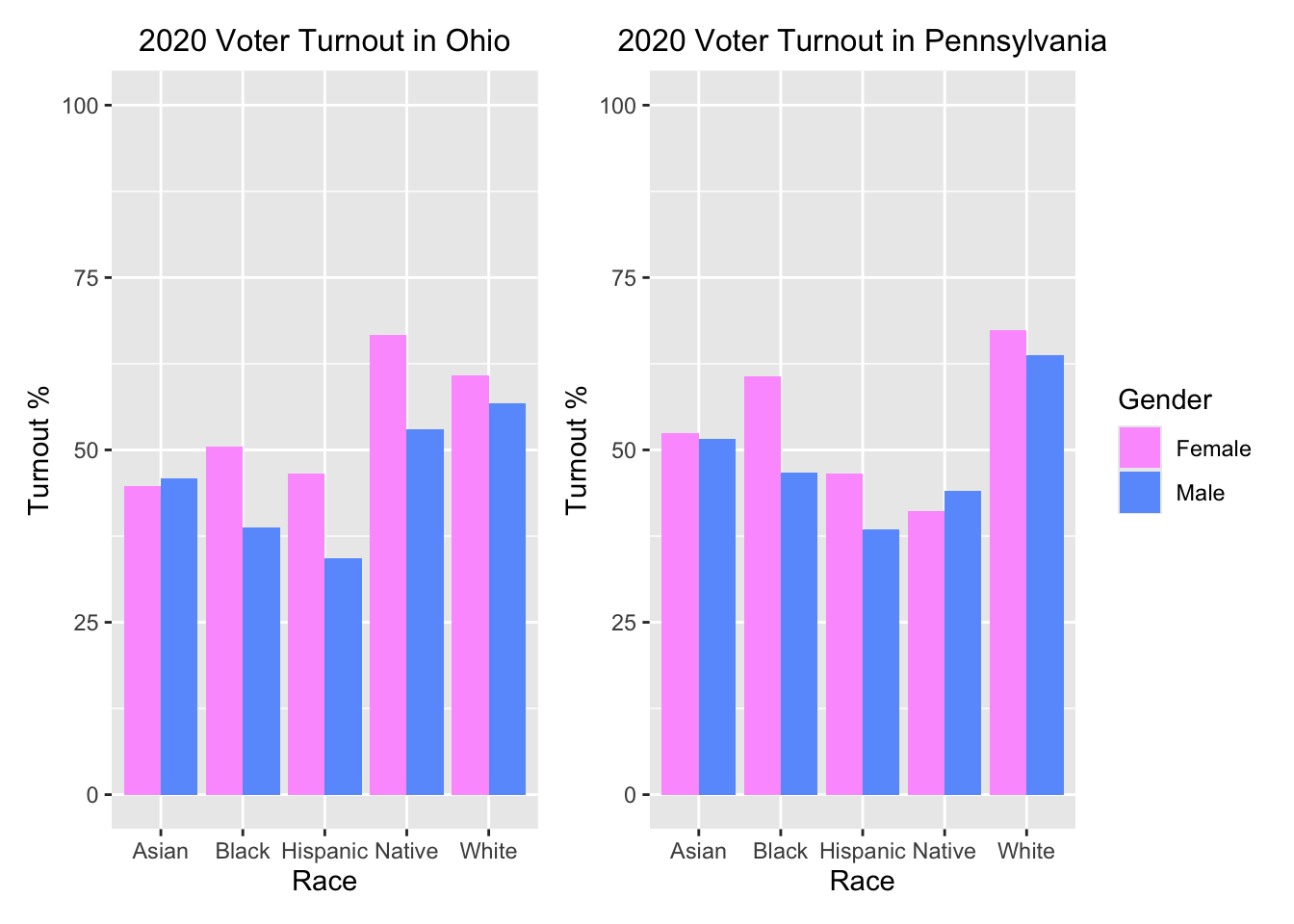

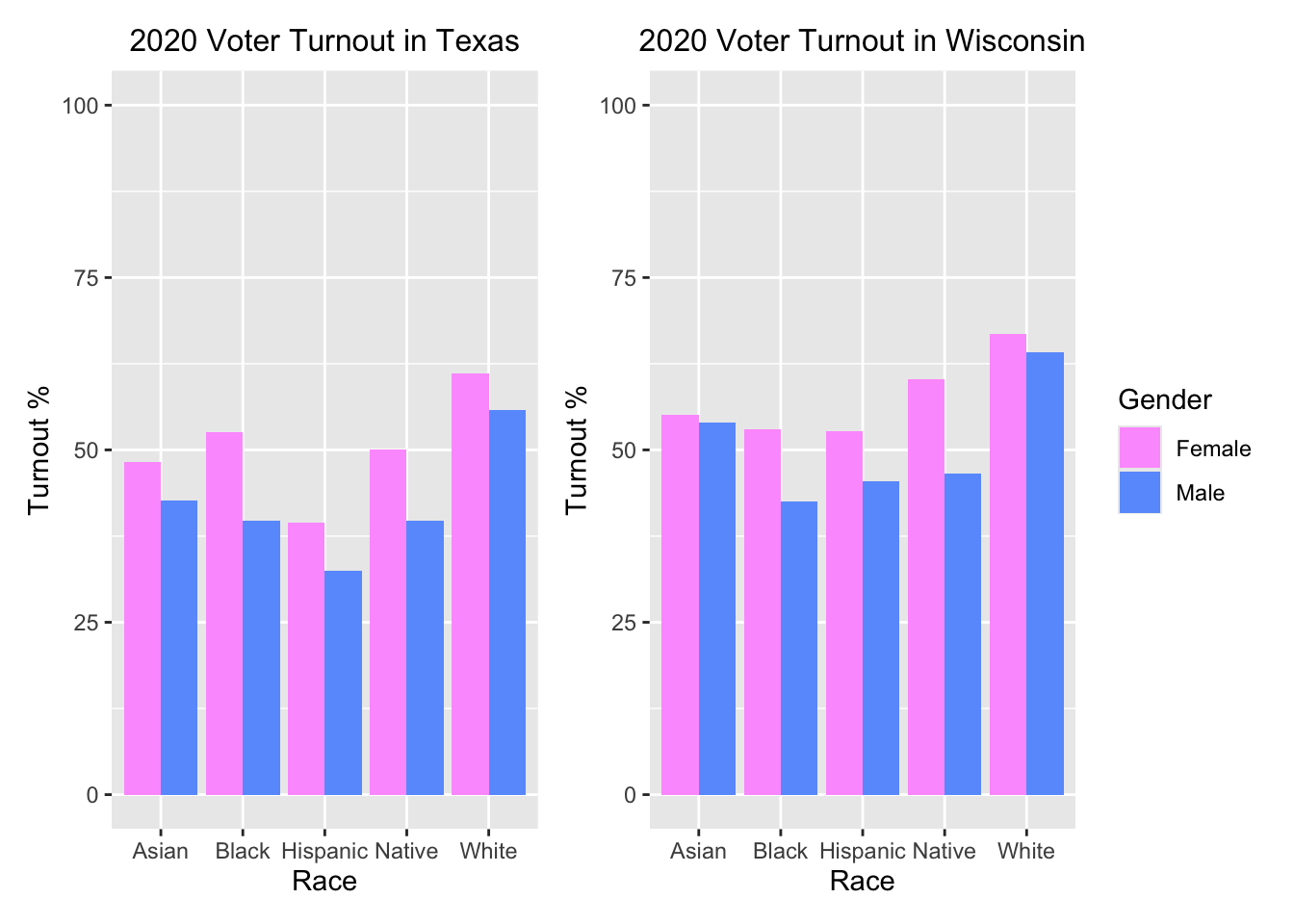

Next, I will briefly look at how different genders and race map onto turnout trends in each of these ten states. Turnout differences between different demographic groups are crucial to understanding how candidates can win, particularly at a time when certain racial groups like Black voters still tend to overwhelmingly favor Democrats and at a time when the gender gap between parties is widening.

As can be seen in the graphs above, among all racial groups and in all 10 key states (besides Ohio Asian-Americans and Pennsylvania Native Americans) women turn out at high rates than men. Furthermore, across these states white voters tend to have some of the highest turnout rates, while Black and Hispanic voters tend to have lower turnout rates. There are some notable exceptions to this. For example, Black women in North Carolina (and to a lesser extent in Pennsylvania) turn out in this sample at almost the same rate as white women in the state. This demographic will be crucial in understanding these electorates, and in future models I will begin to incorporate demographic-based voting trends into my model.

Updated Polling-Based Model

For this week’s predictive model though, I will briefly update my state polling-based model from week 3. I will use the same model as week three, but incorporate the intervening two weeks of additional polling data into my prediction.

| Democratic Party State-Level Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 1.32 | 0.25 | 0.82 – 1.82 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | 1.10 | 0.01 | 1.09 – 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 8391 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.810 / 0.810 | |||

As seen above and as similarly shown in my third blog post, this model has a high R squared value of roughly 0.81, signifying a strong positive correlation between September state-level polling and the final results. Inputting the last few weeks of state-level polling data into this model yields the following results:

| State | Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 52.65 | 30.40 | 74.89 |

| California | 66.66 | 44.42 | 88.91 |

| Florida | 50.92 | 28.68 | 73.17 |

| Georgia | 53.15 | 30.90 | 75.39 |

| Maryland | 69.38 | 47.13 | 91.63 |

| Michigan | 53.83 | 31.58 | 76.07 |

| Minnesota | 55.96 | 33.71 | 78.20 |

| Missouri | 46.91 | 24.67 | 69.16 |

| Montana | 43.87 | 21.63 | 66.12 |

| Nebraska Cd 2 | 57.36 | 35.11 | 79.60 |

| Nevada | 53.04 | 30.80 | 75.29 |

| New Hampshire | 57.30 | 35.06 | 79.54 |

| New Mexico | 56.34 | 34.10 | 78.59 |

| North Carolina | 53.10 | 30.85 | 75.34 |

| Ohio | 48.18 | 25.94 | 70.43 |

| Pennsylvania | 53.61 | 31.37 | 75.85 |

| Texas | 49.89 | 27.64 | 72.13 |

| Virginia | 55.99 | 33.75 | 78.24 |

| Wisconsin | 54.62 | 32.38 | 76.87 |

As can be seen above, Harris fairs very well in this model, winning every one of my previously identified 10 key states except for Texas while boasting strong margins elsewhere. This model also represents a small increase in Harris’ vote share in these states compared with two weeks ago. This said, this model still shows notably large upper and lower bounds, so this prediction must be taken with a grain of salt, especially given how zealous it is for Harris.