Introduction

Every election cycle, billions of dollars are spent on political campaigns up and down the ballot. But for all of the paid staffers, internal polls, and pricey consultants, presidential campaigns’ largest expense is almost always campaign ad spending. Every year, these campaigns battle it out with their ads in the so-called “Air War,” spending hundreds of millions of dollars in key swing states trying to promote themselves and destroy the reputation of their opponents. But questions remain as to how much of an effect these campaign ads actually have in these states. For this week’s blog post, I will investigate this issue of campaign ad spending, looking at past trends to understand what impact ad spending will have in 2024, which is shaping up to easily be the most expensive presidential campaign in history.

Past Campaign Ad Spending

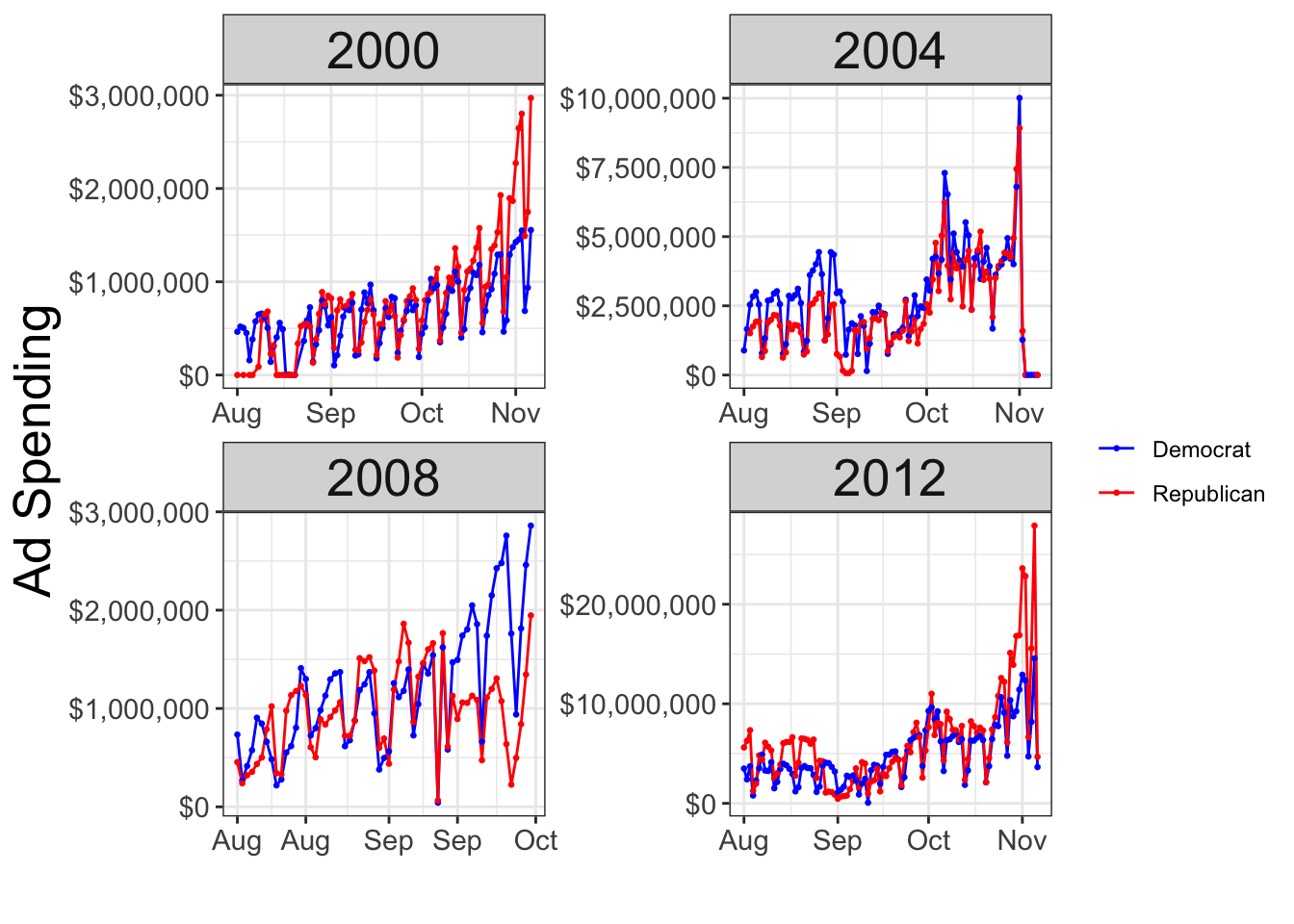

First, let’s look at previous cycles. As you can see in the graphs below depicting how many ads were spent each day during the 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 campaigns, ad spending generally rises as the election progresses, with campaigns particularly ramping up their spending in the final month or two.

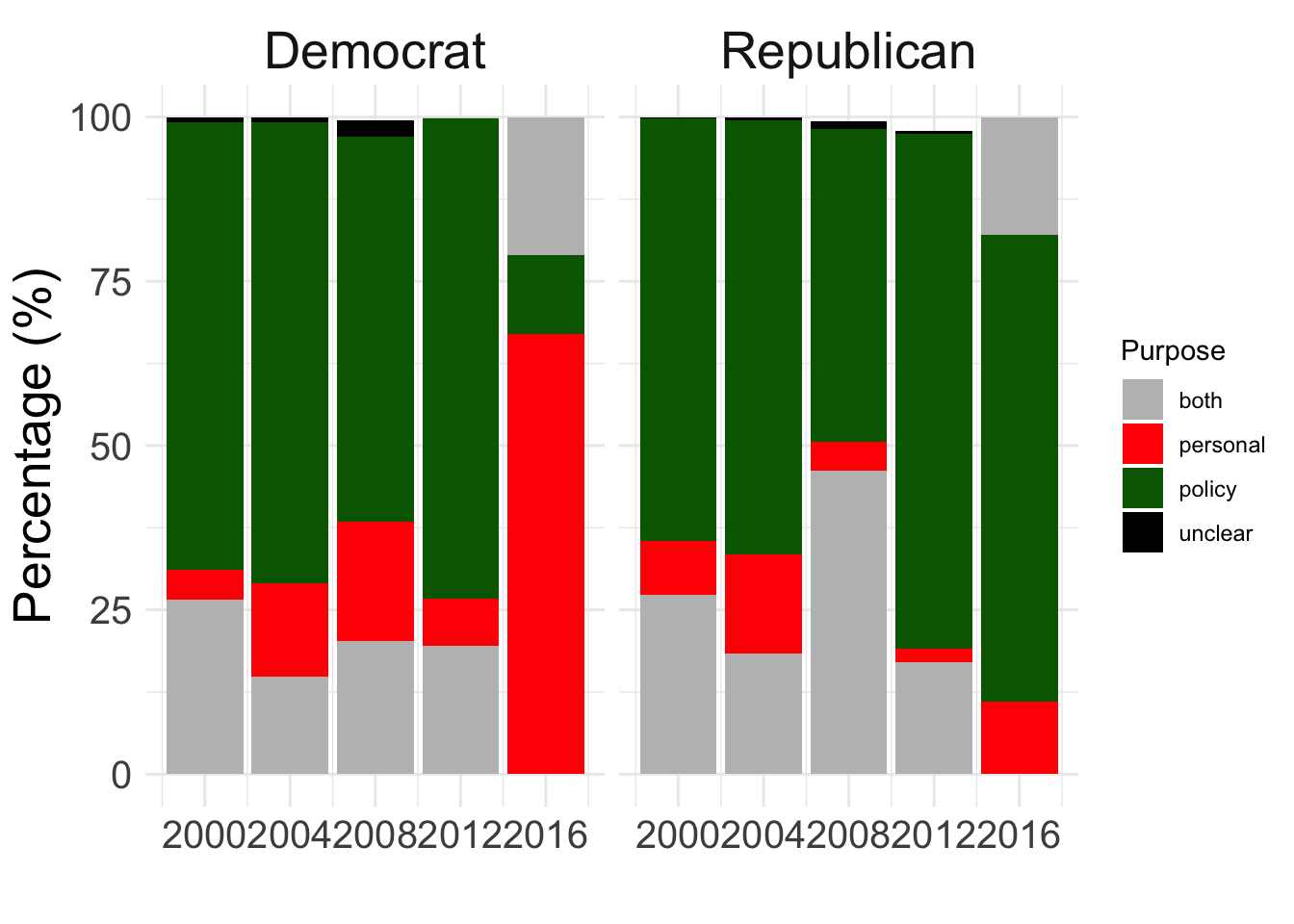

But these graphs showing the total expenditure by each campaign on any given day do not give us the full picture. Campaign ads generally can be divided into three categories, those focused on policy issues, those focused on the candidates themselves, and those focused on both. The chart below shows us how much various campaigns spent on these different types of ads.

As can be seen, candidates generally spend most of their ad spending talking about policy issues important to Americans, with the notable exception being Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign which focused its attack ads heavily on Donald Trump’s character. This said, both policy and personal types of ads can be either positive or negative.

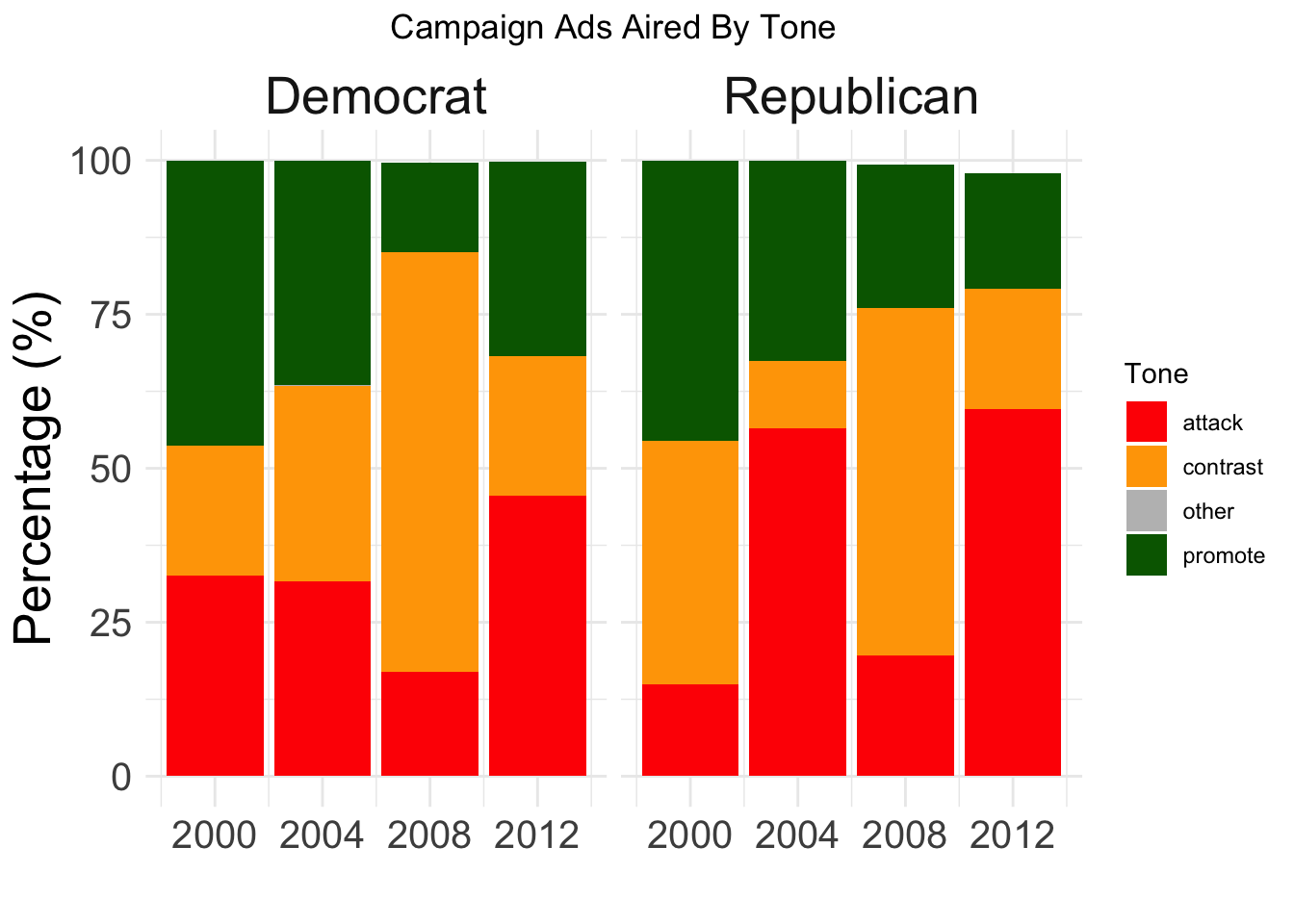

The above chart shows that between 2000 and 2012, both candidates in each race had a healthy balance of types of ads, with notable exceptions being 2008’s heavy focus on contrast ads and the trend towards more negative ads in the more hostile 2012 campaign between Obama and Romney. We can also track the proportion of ads that were used to attack vs promote a candidate over time in these four campaigns:

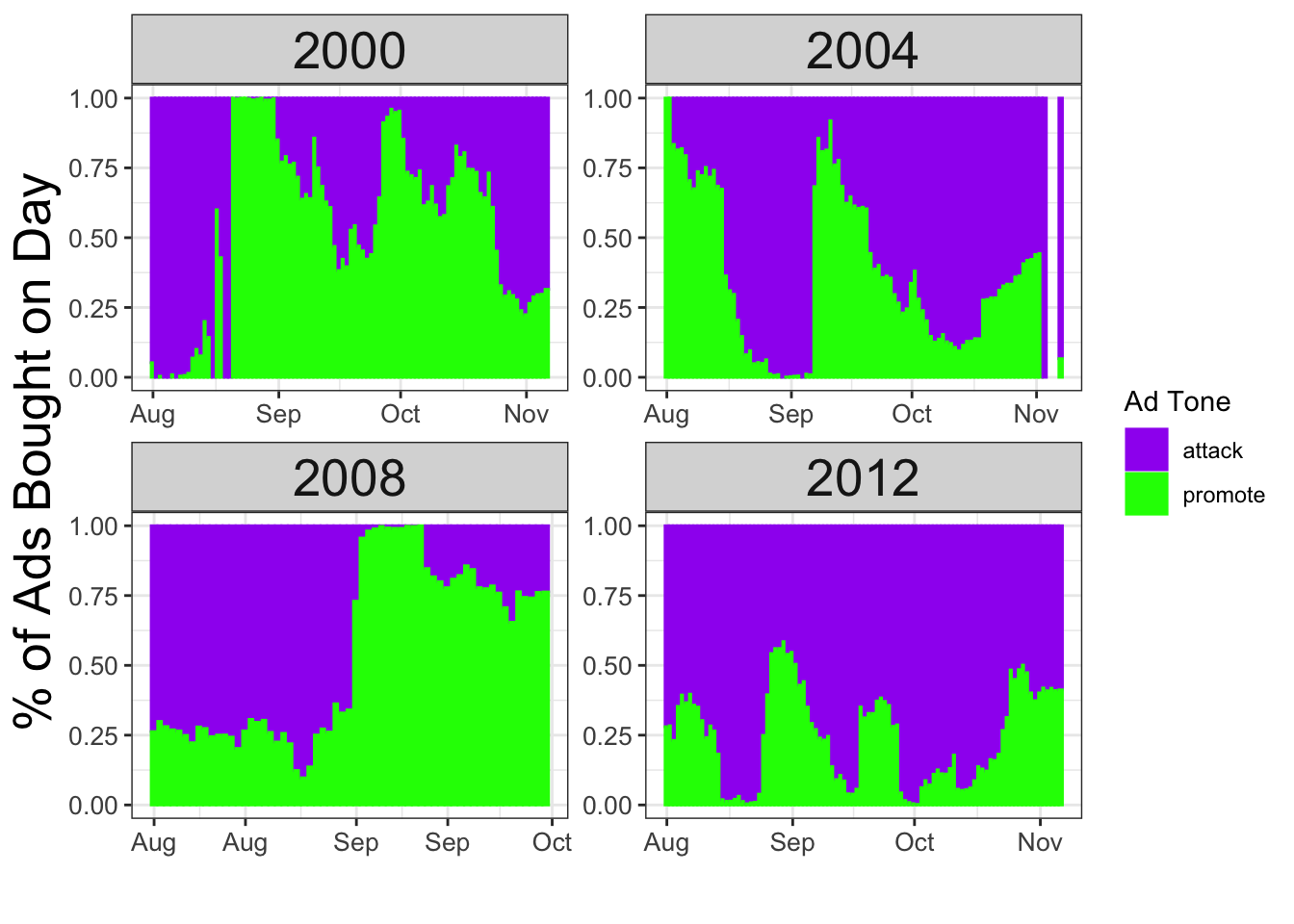

As can be seen, there is great variation between campaigns on the timing of when to attack your opponent or promote yourself. One notable moment out of these four campaigns was the anneversary of 9/11 during the 2004 campaign, at which point the campaigns switched suddenly from airing almost entirely negative ads to airing almost exclusively positive ones.

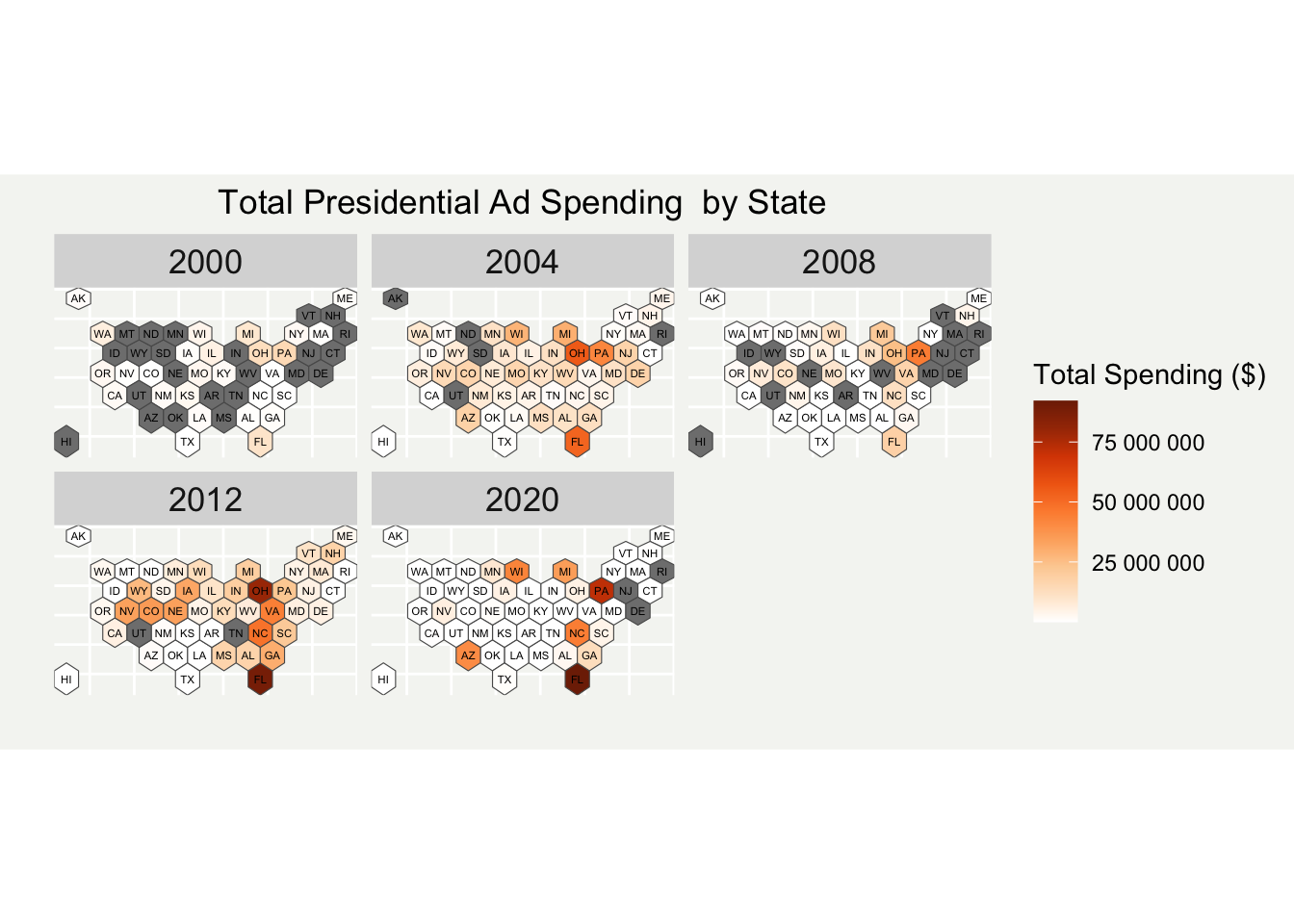

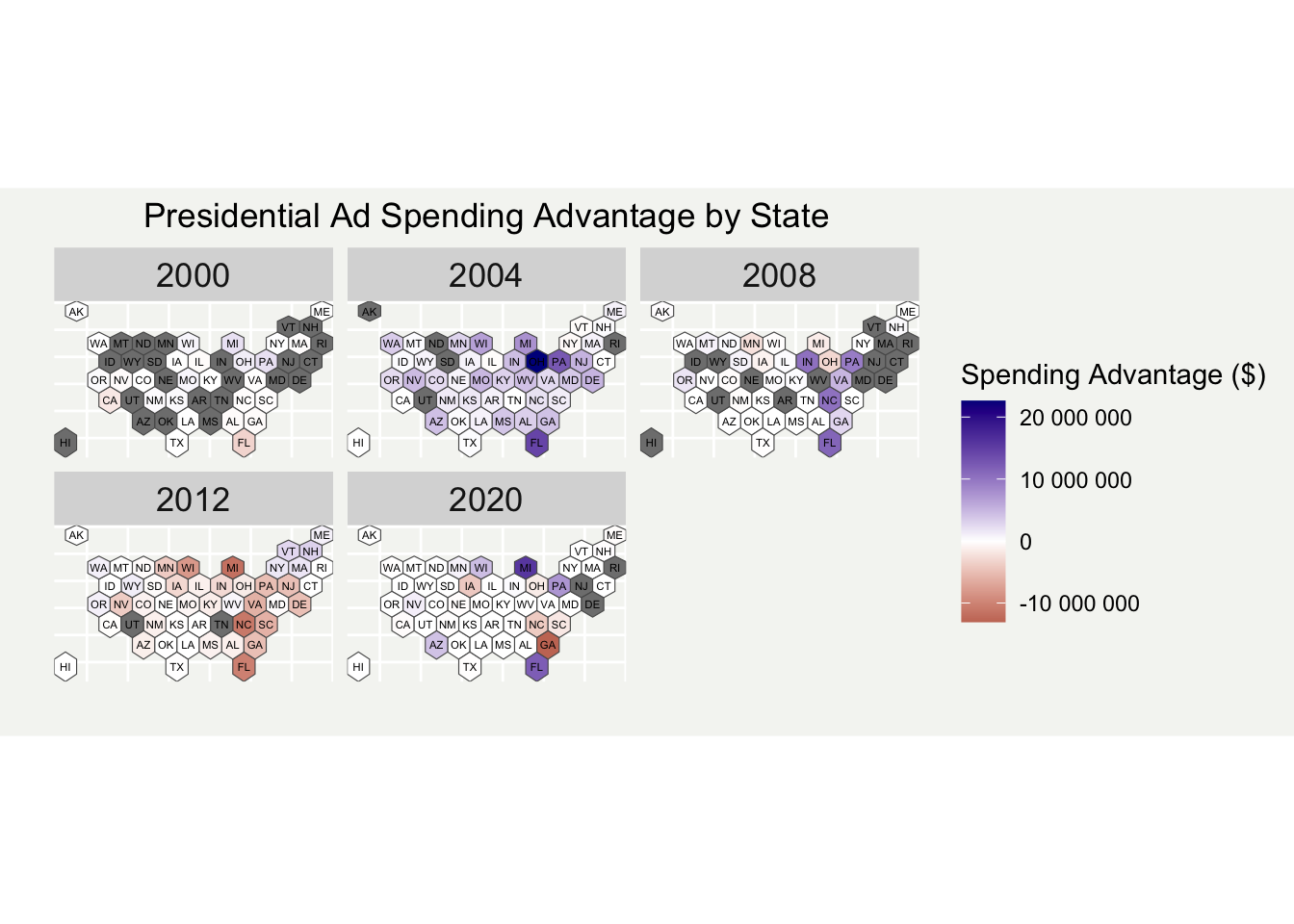

We also can trace the state-by-state expenditure over the years.

As you can see in the maps above, the states that campaigns have targeted with ad spending has changed considerably over time, though certain states, such as Florida, tend to be heavily contested every cycle (although that seems likely to not be the case in 2024). In the maps showing total expenditure, you can also see how total spending has increased over time, with even the most heavily targeted states in 2000, namely Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida, saw much less expenditure than the most hotly contested states in 2020.

Regression Model on Ad Spending

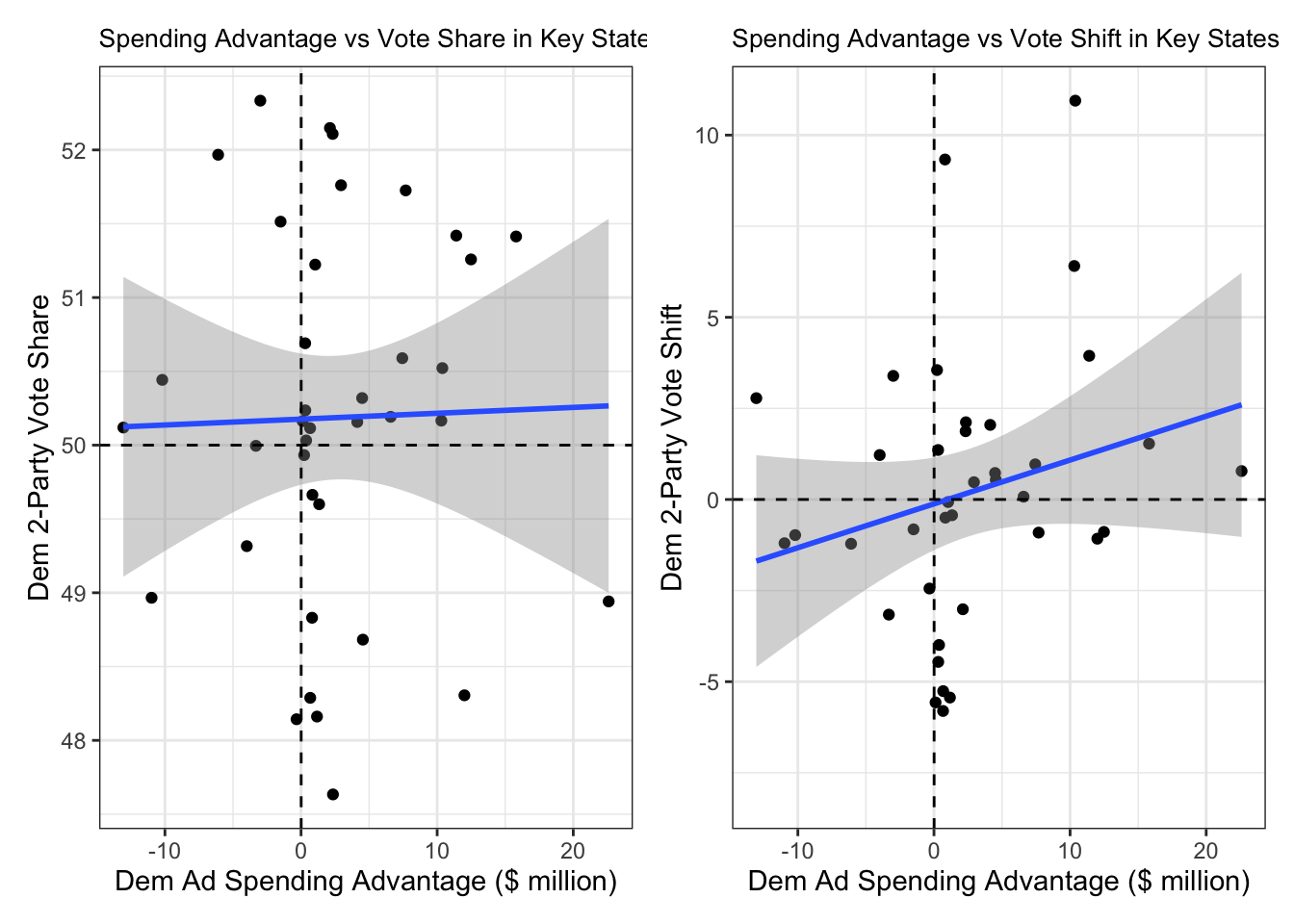

Knowing how much the campaigns have spent in each of the swing states every cycle and thus knowing how much of an advantage each party had in a given state, we can investigate whether these spending advantages had any impact on the election results in these states. Below are to graphs. The first depicts Democratic party spending advantage in states won or lost by less than 5 points between 2000 and 2020 (excluding 2016) compared to their two-party vote share in each said state. The second graph shows the same thing, except instead of the Democratic two-party vote share, it shows the shift towards (or against) Democrats in the two-party vote share compared to the prior election. The trendlines of each of these relationships are also shown.

As can be seen in these two graphs, the relationship between ad spending advantage and vote share is very weak if at all present, and the relationship between spending advantage and shift in how a state votes is slightly stronger but still very weak. If I run three regression models below, a similar story plays out.

| Democratic Two-Party Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 50.18 | 0.22 | 49.73 – 50.62 | <0.001 |

| spending diff adjusted | 0.00 | 0.03 | -0.06 – 0.06 | 0.893 |

| Observations | 38 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.001 / -0.027 | |||

| Democratic Two-Party Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 46.27 | 2.85 | 40.49 – 52.05 | <0.001 |

| spending diff adjusted | 0.01 | 0.03 | -0.05 – 0.07 | 0.664 |

| D pv2p lag1 | 0.08 | 0.06 | -0.04 – 0.19 | 0.178 |

| Observations | 38 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.052 / -0.002 | |||

| Democratic Two-Party Vote Share Shift | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | -0.12 | 0.63 | -1.39 – 1.15 | 0.848 |

| spending diff adjusted | 0.12 | 0.08 | -0.05 – 0.29 | 0.160 |

| Observations | 38 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.054 / 0.028 | |||

The first of these three regression models tests the relationship between the spending difference and the Democrats’ two-party popular vote share. The second model tests the same relationship, but also incorporates the prior year’s election results into the model. The theory behind incorporating this data is that, for example, if there are Republican-leaning states, even if Democrats have an ad spending advantage, Republicans will likely still win the state, so correcting for historical partisan performance is important. The third model tests the relationship between spending difference and vote shift. The logic behind this model is that if Democrats spend a lot of money in a state and have an ad advantage, they might suddenly do better there, potentially explaining the shifts that swing states see from cycle to cycle.

This said, none of these three models find particularly compelling results, will particularly low R squared values in each and flat trendlines in all three. The fit for the third model is slightly less bad, but with a slope of just 0.12 and an adjusted R squared value of 0.028, any relationship that exists would be small and weak.