Introduction

Campaigns every year spend billions of dollars trying to convince registered voters to both turn out and choose their prefered candidate. While the largest campaign expense every year is the air war, which I covered last week, campaigns also spend significant resources trying to win the so-called “Ground Game.” This week, I will look into the role of field offices and campaign stops before then updating my national popular vote model and state by state model.

The Ground Game

Field Offices

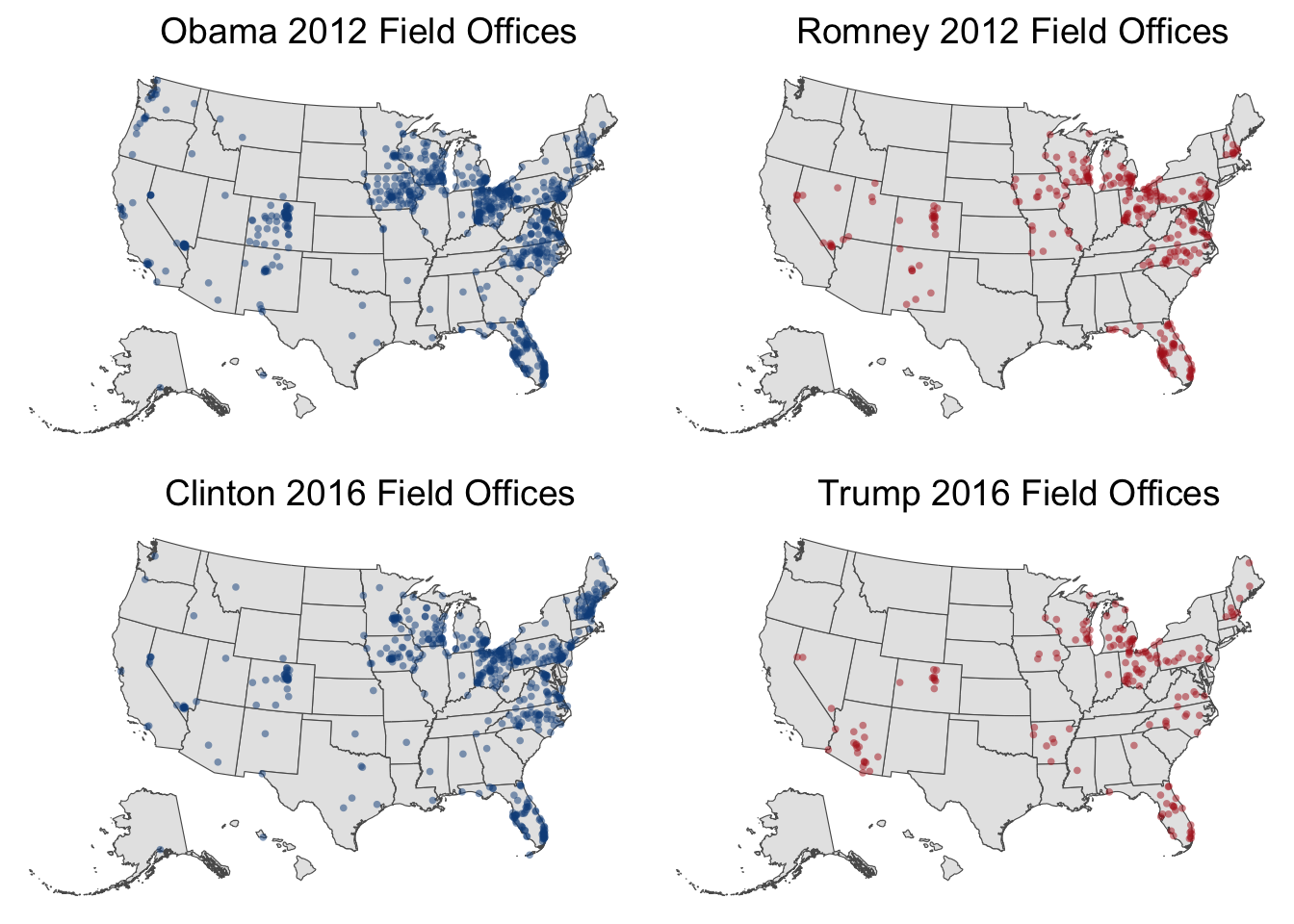

To begin our analysis of the ground game, let’s explore the role that field offices play. These offices serve as the local hubs for campaigns and their volunteers to go out and knock on doors, put up signs, and generally conduct what many people see as the on the ground element of a campaign. Obviously, not having a physical presence in an area means that you are not fighting on the ground for those voters’ support, whereas if both campaigns have numerous offices in an area it is clear how contested that region is. Let’s look at the geographic distribution of field offices in 2012 and 2016.

Above we can see the shifting nature of where the campaigns considered to be battleground states. In 2012, Obama had numerous field offices in Dem-leaning states like New Mexico, Colorado, and Oregon while in 2016 Clinton pulled back her efforts in those states. We also can see the emergence of Arizona as a battleground, with Romney not having any Arizona field offices in 2012 but Trump ramping up efforts in the state four years later, with the inverse being true for Maine, where Obama barely had any offices and Romney did not contend, but Clinton had to defend the state heavily and only won by a 3% margin.

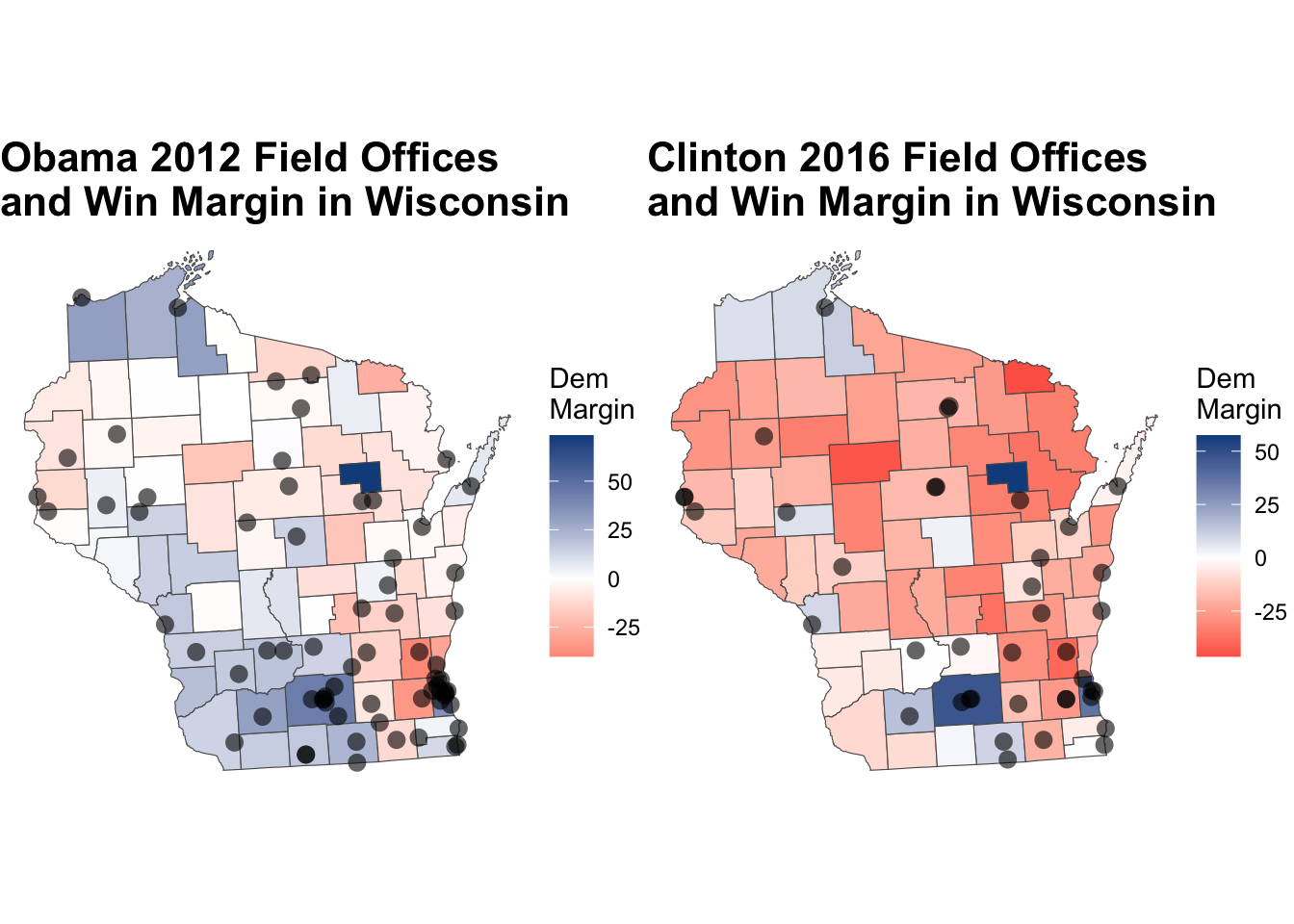

We can also look closer within states. For example, in the perennial battleground state of Wisconsin, the 2016 Clinton campaign had notably fewer field offices, particularly in numerous rural areas in the north, northwest, and southwest. This change, as can be seen in the graphs below, correlated with a massive Democratic collapse in rural areas. Of course, this is not entirely due to the reduced ground presence, as Democratic collapse among working-class white voters in 2016 happened across the board. Even if one were to claim that there is no causal effect, it is clear that field offices are important for understanding campaigns’ strategies.

Campaign Events

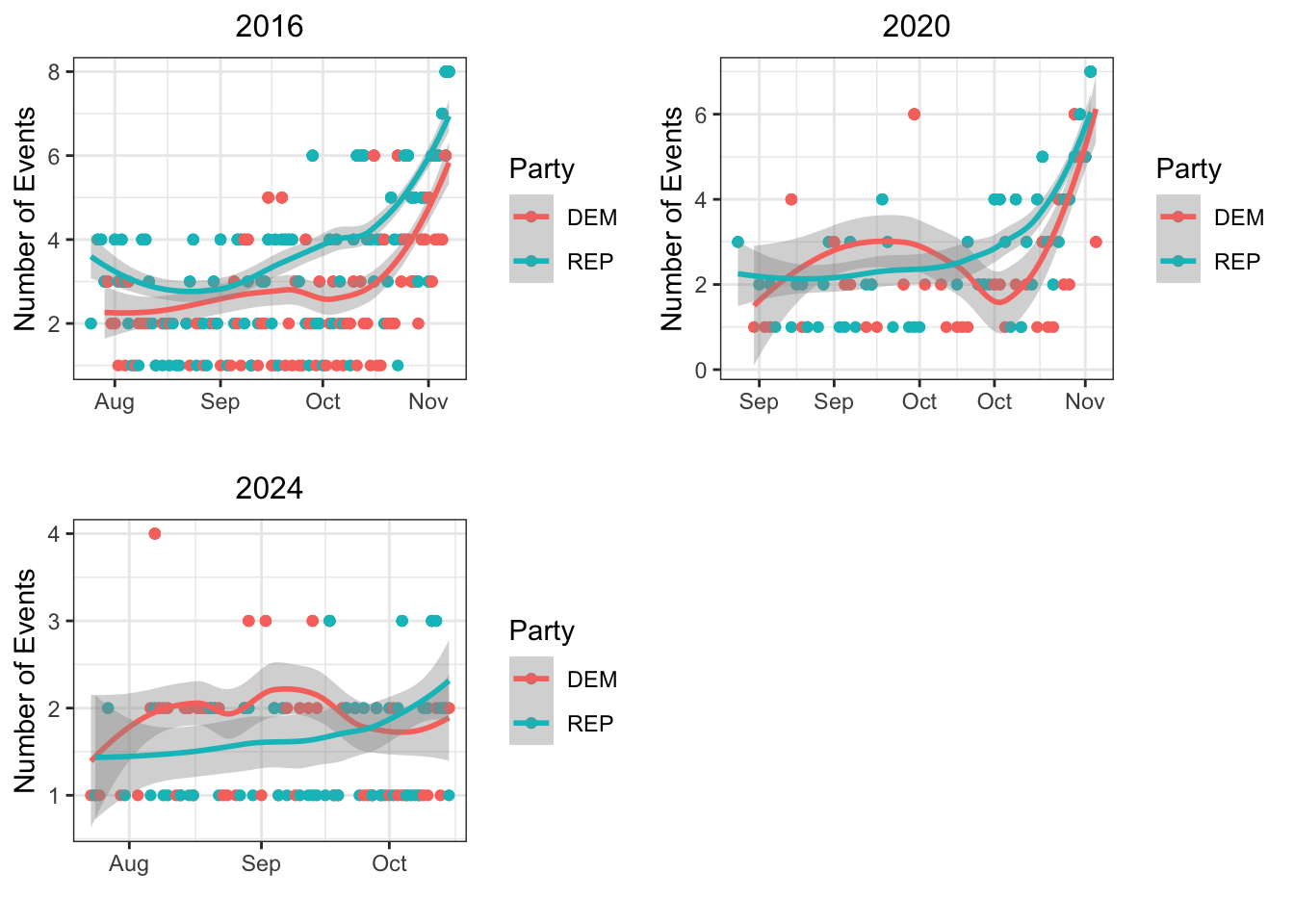

Another crucial way that the group war is waged is with campaign events involving the candidate themselves. We can first graph these events over time. In the three graphs below, we can see how the number of these campaign events ramp up in the final month or so, and now during the 2024 cycle we can see the beginnings of this upswing in events too.

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula = 'y ~ x'

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula = 'y ~ x'

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula = 'y ~ x'

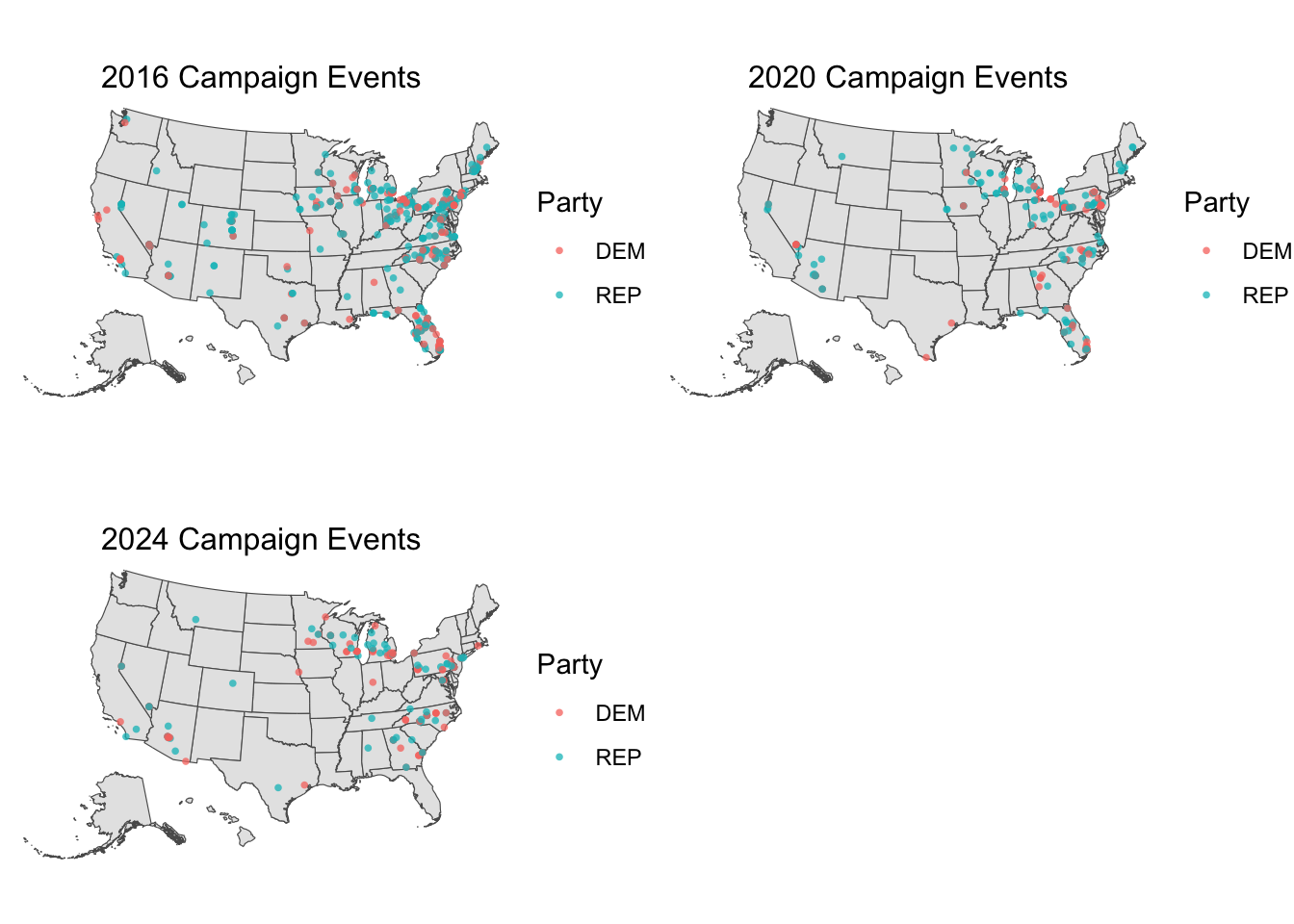

Obviously though, campaign events are tied to specific locations, meaning we can plot where on the map these events take place, which I have done below for the 2016, 2020, and 2024 (so far). Once again, and even moreso than with the field offices map, we can see how these campaigns strategically target events in the states they view as competitive, with the Midwest battlegrounds, North Carolina, Nevada, Arizona, and (to a lesser extent in 2016) Georgia featuring heavily in all three election cycles. We also can clearly see how neither campaign believes that Florida is in play this cycle, or at least not in play enough to warrent spending the principle’s valuable time.

Updating Models

National 2-Party Popular Vote Model

Finally, it is time for me to update my 2024 model. This week I am combining updated polling data but also factoring in Quarter 2 economic performance and the incumbency effect. Now that we are only about 2 weeks away from the election, we are beginning to incorporate polls that are being weighed heavily due to the historical accuracy of polls near to election day.

| National 2-Party Vote Share for Incumbent Party | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 28.28 | 4.20 | 18.78 – 37.79 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | -0.01 | 0.32 | -0.73 – 0.71 | 0.977 |

| oct poll | 0.51 | 0.31 | -0.18 – 1.20 | 0.130 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.13 | 0.08 | -0.05 – 0.30 | 0.132 |

| incumbent | 0.35 | 1.46 | -2.96 – 3.65 | 0.818 |

| Observations | 14 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.835 / 0.762 | |||

This model has an R squared value of 0.84 and an adjusted R squared value of 0.76, meaning that there is likely a strong predictive effect of the model. This said, these R squared values are lower than they might otherwise be because of the presence of the 2020 GDP growth outlier data point, but I made the decision to include that data point because even if it might make my trendline fit slightly less well, the chaotic nature of today’s politics and economic realities may mean that the predictive power of Q2 GDP growth moving forward may be more in line with the 2020 effects than with prior trends, and I wanted to incorporate that uncertainty into my model.

If we then use 2024 data, including 2024 polling data up until this day, we get the following national 2-party vote share result for Harris:

| Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 52.85314 | 46.85147 | 58.85482 |

This would represent about a 5.5% 2-party national vote share victory over Trump, which although a slight decrease from Biden’s 2020 margin, still represents a strong national popular vote victory in today’s calcified political environment. This model also has more constrained bounds than many of my previous models, which is of note.

State 2-Party Model and Electoral College

Moving on to the state level, I use the same variables: polling data, GDP performance, and incumbency effect.

| State 2-Party Vote Share for Democrats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | -2.76 | 1.25 | -5.22 – -0.31 | 0.028 |

| sept poll | 0.05 | 0.17 | -0.29 – 0.38 | 0.779 |

| oct poll | 1.13 | 0.16 | 0.81 – 1.45 | <0.001 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.13 – 0.21 | <0.001 |

| d incumbent | 0.18 | 0.52 | -0.85 – 1.21 | 0.727 |

| Observations | 191 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.921 / 0.919 | |||

This model seems even more predictive, with an R squared value and an adjusted R squared value of 0.92, with state level October polling being particularly predictive. When we apply 2024 data to this model we get the following results:

| State | Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 52.79599 | 46.92425 | 58.66774 |

| California | 67.66514 | 61.72463 | 73.60564 |

| Florida | 51.26466 | 45.40155 | 57.12777 |

| Georgia | 53.29166 | 47.41821 | 59.16511 |

| Maryland | 70.70724 | 64.74939 | 76.66510 |

| Michigan | 54.13417 | 48.26183 | 60.00652 |

| Minnesota | 56.42838 | 50.55066 | 62.30610 |

| Missouri | 46.66412 | 40.79641 | 52.53183 |

| Montana | 43.65292 | 37.78582 | 49.52002 |

| Nebraska | 41.07555 | 27.31091 | 54.84020 |

| Nebraska Cd 2 | 57.78784 | 51.90186 | 63.67381 |

| Nevada | 53.95362 | 48.09405 | 59.81318 |

| New Hampshire | 57.83063 | 51.94734 | 63.71392 |

| New Mexico | 56.74991 | 50.86887 | 62.63095 |

| New York | 58.47675 | 40.20306 | 76.75044 |

| North Carolina | 53.45914 | 47.59041 | 59.32787 |

| Ohio | 48.54860 | 42.68988 | 54.40733 |

| Pennsylvania | 54.18112 | 48.31485 | 60.04740 |

| Texas | 49.81926 | 43.95067 | 55.68786 |

| Virginia | 56.72388 | 50.85122 | 62.59653 |

| Wisconsin | 54.56411 | 48.67910 | 60.44912 |

Under this model, Harris wins all 7 key swing states in addition to taking Florida and only narrowly losing Texas. This would translate to a landslide 349-139 vote victory in the Electoral College. This said, while the bounds for these results are narrower than my previous state-level results they still show a wide range of possibilities, with all seven key swing states within the range of a Trump victory even in this model that clearly is favorable to Harris.