Introduction

We are now only one week away from the election. Thus, this week I will first briefly explore the role that so-called “shocks” and “October Surprises” have on elections. Every election year, unexpected events happen that may or may not significantly affect the election, but they are usually near impossible to predict and/or equally hard to quantify, which is why I will discuss their role generally in elections and discuss some events in the 2024 campaign that could be considered “shocks” before then dedicating more time to updating my model and expanding it to all 50 states.

Shocks

Historically, people have argued that things as seemingly small and apolitical as high school football game victories and shark attacks and that things as monumental and/or calamitous as hurricanes and pandemics should be considered “shocks.” As we have discussed in class, the actual effects of smaller, more localized events, like the first two examples, is heavily disputed. However, many larger apolitical events like natural disasters and, predictably, many notable political events (particularly those that occur in the final month of the campaign) clearly have impacts.

Obviously, it is almost impossible to determine any causal effects from these shocks and October surprises, but let’s briefly explore some key events from the 2024 election that we may consider to be shocks. In terms of political events, we can definitively say that Biden’s performance in the first presidential debate and his subsequent withdrawal from the race were sudden shocks that upended the race. There were also some political shocks whose effects are unclear, such as the two assassination attempts against Trump. There also have, and in the next week likely will be more, political shocks happening in the home stretch, such as the anti-Puerto Rican joke made at Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally the night of the 27th, and we will not know the effects of the these late-emerging shocks until after the election, if ever. In terms of apolitical shocks from this cycle, the clear frontrunner is Hurricane Helene, which wroght destruction to much of western North Carolina and parts of Georgia, two crucial swing states in the election. Already, there are reports of lower turnout in the affected regions, which, in a close election, might prove decisive.

Electoral Model

National 2-Party Popular Vote Model

For my national model, I have updated it to include new polling additions from the last week. I played around with adding certain other variable, such as the incumbent president’s approval rating and quarter 2 RDI growth, but I decided against including these because, in the case of the former, I believe President Biden’s approval numbers are disproportionately dragged down by perceived ineffectiveness of his age and that Harris, who enjoys on average an even (if not positive) approval rating is uniquely insulated from this outlier data point compared to prior elections. In the case of the latter, I chose not to include RDI growth given previously concerns about how predictive it is and whether it overlaps too much with GDP growth. I also made the decision, unlike my model from last week, to exclude the 2020 election from my model. This is because I believe that the economic outlier situation in 2020 was unrepresentitve of typical trends. As such, below is the regression table for my updated model:

| National 2-Party Vote Share for Incumbent Party | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 30.87 | 3.75 | 22.22 – 39.52 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | -0.21 | 0.28 | -0.87 – 0.45 | 0.484 |

| oct poll | 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.01 – 1.22 | 0.048 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.07 – 0.83 | 0.025 |

| incumbent | 1.00 | 1.27 | -1.94 – 3.93 | 0.456 |

| Observations | 13 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.891 / 0.836 | |||

As can be seen, my model is still a significant predictor of past election results, with an adjusted R squared value of 0.917. When applied to 2024 polling data, GDP growth, and incumbency, I predict the following share of the two party national popular vote for Harris:

| Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 51.8823 | 46.60423 | 57.16036 |

This represents about a 1 point decrease in her share of the 2-party national popular vote compared to my model last week, though the upper and lower bounds clearly show that it is clearly possible for Harris to win by more come next Tuesday night or to outright lose the national popular vote.

State 2-Party Model and Electoral College

Moving on to my state-level model, I have made a few changes this week. First, I have added in electoral lag into my model, adding in variables that factor in how states voted in 2020 and 2016. In addition to that, I have continued to include the September and October polling numbers, the GDP quarter 2 growth, and the incumbency factor into my model below:

| State 2-Party Vote Share for Democrats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | -3.47 | 1.00 | -5.44 – -1.49 | 0.001 |

| sept poll | -0.15 | 0.11 | -0.36 – 0.07 | 0.178 |

| oct poll | 0.95 | 0.12 | 0.72 – 1.18 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag1 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.21 – 0.44 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag2 | 0.02 | 0.04 | -0.06 – 0.10 | 0.563 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.07 – 0.13 | <0.001 |

| d incumbent | -0.88 | 0.47 | -1.81 – 0.04 | 0.061 |

| Observations | 290 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.935 / 0.934 | |||

As can be seen above, my model is one again highly predictive, with an adjusted R squared value of 0.934. When applying this to the 2024 election for states that we have polling for, we get the following:

| State | Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 50.99701 | 45.96480 | 56.02922 |

| California | 66.35129 | 61.25790 | 71.44468 |

| Florida | 49.42892 | 44.38904 | 54.46879 |

| Georgia | 51.30020 | 46.26385 | 56.33655 |

| Maryland | 69.09056 | 64.00166 | 74.17946 |

| Michigan | 52.37408 | 47.33991 | 57.40825 |

| Minnesota | 54.68925 | 49.65307 | 59.72543 |

| Missouri | 44.02709 | 38.97850 | 49.07567 |

| Montana | 41.79470 | 36.76266 | 46.82674 |

| Nebraska | 40.72778 | 35.68590 | 45.76965 |

| Nebraska Cd 2 | 55.44722 | 50.39503 | 60.49942 |

| Nevada | 52.32526 | 47.28961 | 57.36092 |

| New Hampshire | 55.66123 | 50.61341 | 60.70904 |

| New Mexico | 55.59479 | 50.56292 | 60.62667 |

| New York | 60.74034 | 55.68942 | 65.79125 |

| North Carolina | 51.20562 | 46.16098 | 56.25026 |

| Ohio | 46.74829 | 41.71675 | 51.77983 |

| Pennsylvania | 52.17702 | 47.13659 | 57.21746 |

| Texas | 47.92379 | 42.89250 | 52.95508 |

| Virginia | 55.46919 | 50.44100 | 60.49738 |

| Wisconsin | 52.23845 | 47.18666 | 57.29024 |

As can be seen, not only do we have a few more states represented here than my model from last week, but we also have some shifts. Notably, Florida has now shifted out of Harris’ column into Trump’s, with Texas and Ohio falling deeper into his column and the 7 key swing states all falling back within a 5-point margin, with Arizona now under a 2-point margin.

Another key change I have made to my model this week is that I have added in a secondary model for states that do not have polling available for the 2024 election. This model thus includes the other four variables I put into my first state-level model. The regression table for this second model is below:

| State 2-Party Vote Share for Democrats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 3.57 | 1.04 | 1.51 – 5.62 | 0.001 |

| D pv2p lag1 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 1.00 – 1.21 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag2 | -0.13 | 0.05 | -0.24 – -0.02 | 0.016 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.02 – 0.05 | 0.490 |

| d incumbent | -4.63 | 0.53 | -5.67 – -3.58 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 255 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.918 / 0.917 | |||

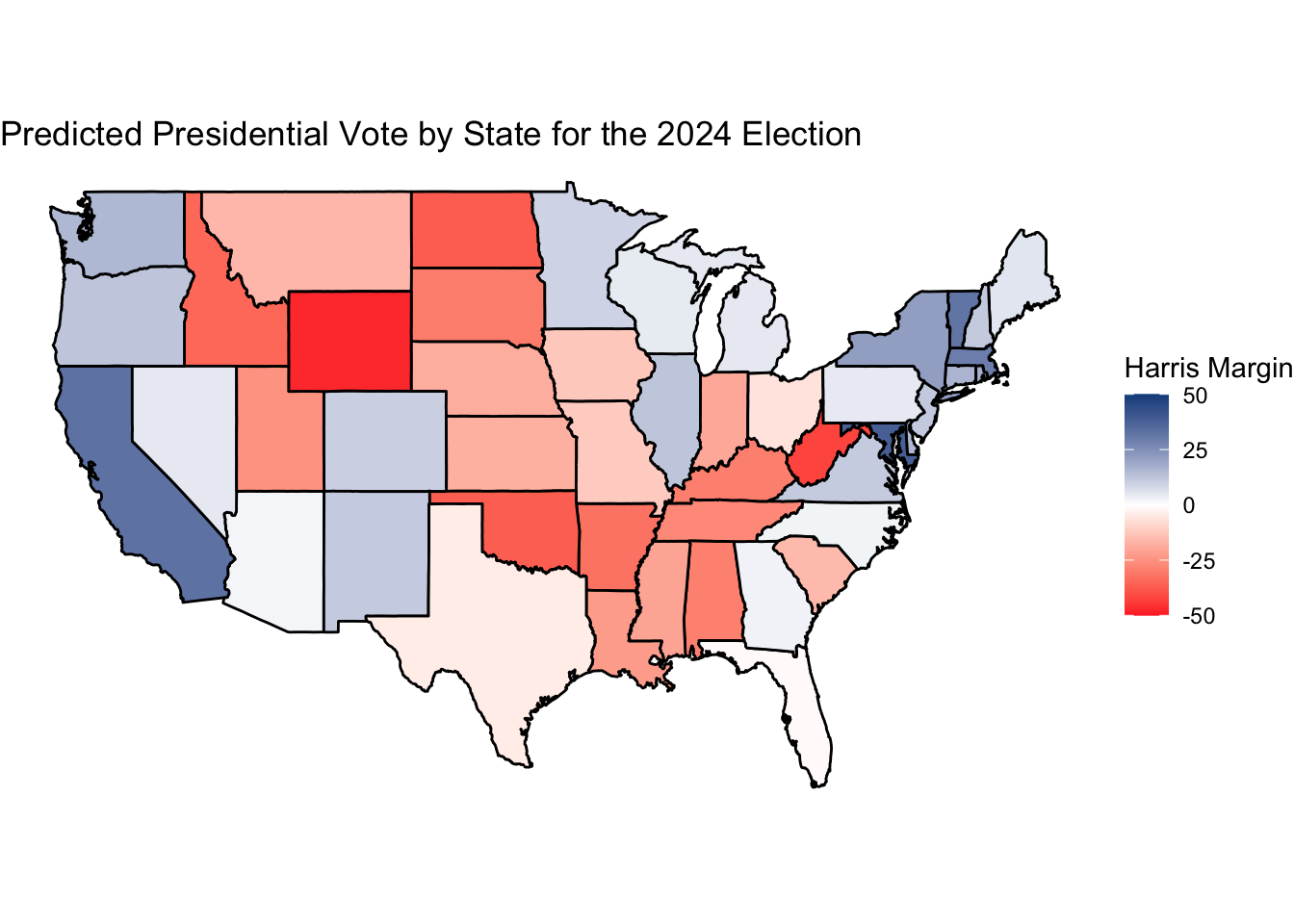

As can be seen, this model is still highly predictive of results, albeit slightly less than the first model and relying heavily on the 1-cycle lag variable. Nonetheless, it is a useful indicator, and when I apply this to 2024 numbers for the states without polling numbers and map the results of the results of the two models, we get the below electoral map:

This map (which does not show Trump-won Alaska or Harris-won Hawaii or DC, and which does also not show margins in NE02 or ME02, which would go to Harris and Trump respectively) shows a Harris electoral college victory 319-219 over Trump.