Introduction

For this week’s blog post, the day before the 2024 election, I will make my final predictions for the national two-party popular vote, state-level two-party popular vote shares, and the associated electoral college vote. Altogether, my predictions are based off of three models, all multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, that hopefully together will paint an accurate picture of what the results will be tomorrow (or whenever we actually end up getting results).

National Model and Prediction

Equation and Variables

Let’s begin with my national popular vote prediction. This model is built to predict what percentage of the two-party national popular vote will go to the candidate from the incumbent party. This vote share is the dependent variable. In terms of independent variables for this OLS model, I used the following four:

- October Polling Average: The average of national polls taken in October, as compiled by 538, and weighted by how many weeks were left until the election.

- September Polling Average: The average of national polls taken in September, as compiled by 538, and weighted by how many weeks were left until the election.

- Quarter 2 GDP Growth: The percent national GDP growth in Q2 of the respective election year, as provided by the Federal Reserve.

- Incumbency: If the candidate is the incumbent president or not (in addition to being from the incumbent party).

Thus together, the equation for my model is:

$$ \mathbf{National\ Two-Party\ Vote\ Share\ for\ the\ Inc.\ Party} = \mathbf{\beta_0} + \\ \mathbf{\beta_1} \textbf{ Oct.\ National\ Polling\ Average} + \mathbf{\beta_2} \textbf{ Sept.\ National\ Polling\ Average} + \\ \mathbf{\beta_3} \textbf{ Q2\ GDP\ Growth} + \mathbf{\beta_4} \textbf{ Incumbency} + \mathbf{\epsilon} $$Justification of National Model

October Polling Average: Although the accuracy of political polling has been repeatedly called into question, especially over the past few years following notable mishaps in the polling industry in 2016 and 2020, they remain perhaps our best indicator of what electorates are believing at any given point. This said, polling tends to become more accurate as election day approaches, as found by Gelman and King (1993). This is why I have weighted my October polling average by each day, favoring polls on days closer to election day.

September Polling Average: I made the decision to include a September polling average, despite Gelman and King’s findings, because of recent criticisms within the polling industry about two things. First, there are concerns about poll “herding” as the election gets near, with polling agencies being accused of ignoring results that would be outliers and favoring results that either align with other polls or show a closer race. Particularly after the polls supposedly missed in 2016 and 2020, some believe that polling firms are showing a tightening race between Harris and Trump in the last month because these polling agencies got burnt in the last two presidential cycles by overestimating Democrats’ strength and would rather underestimate Harris than once again overestimate Democrats. The second reason is that in recent cycles, particularly in 2022, we have influxes of partisan-funded polls right before the election with the accused intention of wanting to artificially change poll averages to favor their candidate. Thus, for both of these reasons, I wanted to include a September polling average independent variable, knowing that historically it was a worse predictor, because I am concerned for the above two reasons that October polling may be less accurate this time around. By including an average from September, from before polling began to herd and be biased by partisan polls supposedly, I hope to mitigate the impact on my model that any incorrect last-minute shift in the polls may bring.

Quarter 2 GDP Growth: As always, the economy is front and center in politics in 2024. Voters care about the strength in the economy, and, as Achen and Bartels (2014) note, if the economy is weak then voters tend to blame the incumbent party. If the economy is strong, on the other hand, the incumbent party does relatively better. As explored in previous blog posts, I have settled on using Quarter 2 GDP Growth as a barometer for the economic fundamentals of a campaign both because it has a better predictive track record based off of past elections but also because I believe it is a better, more holistic measurement of strength in the economy rather than other proposed measures such as RDI growth. Quarter 2 is used here because it is recent enough to be in voter’s memories, but long enough ago that it defines their perception of the economy under the incumbent party in a way that Q3 would not, as any sudden upswing or downturn in Q3 could likely be waved off by the incumbent party as having been out of their control, or the effects of such a change in the economy may not have had time to trickle down to voters just yet.

Incumbency: Although literature and expert opinions on the role of incumbency are split on whether it has an affect and, if so, whether such an effect is positive or negative. Some claim that the President’s superior ability to fund-raise, to gain free media attention, and to otherwise wield the powers of the Presidency to the advantage of them or of their constituents/potential supporters gives the incumbent president an advantage going into reelection. Others claim that voters can blame the president for any problems facing the country. Others believe any such impact one way or the other is minute, irrelevant, or self-balanced. I believe that the role of incumbency does matter, which is why I have included it in my model, and that we need to look no further than President Biden’s dramatic exit from the 2024 race this past summer to see the importance of whether an incumbent president, for all their faults or strengths, runs for reelection.

Regression Table

I based my model off of data spanning from 1968, when polling data from 538 begins, to the 2016 election. I made the decision to exclude the 2020 election because the economic data from Quarter 2 is such an outlier due to the Covid pandemic that it substantively, and in my opinion unrepresentatively, changed my model when included. Thus, based off of the aforementioned four independent variables and the 13 elections spanning 1968-2016, below is the regression table for my model:

| National 2-Party Vote Share for Incumbent Party | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 30.87 | 3.75 | 22.22 – 39.52 | <0.001 |

| oct poll | 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.01 – 1.22 | 0.048 |

| sept poll | -0.21 | 0.28 | -0.87 – 0.45 | 0.484 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.07 – 0.83 | 0.025 |

| incumbent | 1.00 | 1.27 | -1.94 – 3.93 | 0.456 |

| Observations | 13 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.891 / 0.836 | |||

In terms of how we interpret the above coefficients for each of the four IV’s:

October Polling Average: For every 1-point increase in the incumbent candidate’s weighted October national polling average, we can expect an 0.61-point increase in their eventual national two-party vote share. With a p-value of 0.048, this is one of the two statistically significant IV’s in my model at a 95% confidence interval.

September Polling Average: For every 1-point increase in the incumbent candidate’s weighted September national polling average, we can expect an 0.21-point decrease in their eventual national two-party vote share when controlling for other variables including the October polling average. This last point is important to note. With a p-value of 0.484, this is not statistically significant, but that does not mean that the inclusion of this variable does not add value to my model, as explained previously.

Quarter 2 GDP Growth: For every 1% increase in Quarter 2 GDP growth, there is an associated 0.45-point increase in the incumbent party candidate’s November national two-party vote share. With a p-value of 0.025, this is the second of the two statistically significant IV’s in my model at a 95% confidence interval.

Incumbency: For every 1% increase in “incumbency” there is an associated 1.00-point increase in the incumbent party candidate’s national two-party vote share. This may not initially make much sense, but consider that, of course, there is no such thing as a “1% increase in incumbency” as this is a binary variable. With a p-value of 0.456, this too is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval, but just like the September polling average, that does not mean it does not add value to my model.

Validation

For in-sample error, my model’s R-squared value of 0.89 means that 89% of changes in national two-party popular vote share is explained by my model, representing a pretty strong correlation. This correlation holds strong when adjusted, with an adjusted R-squared value of 0.84.

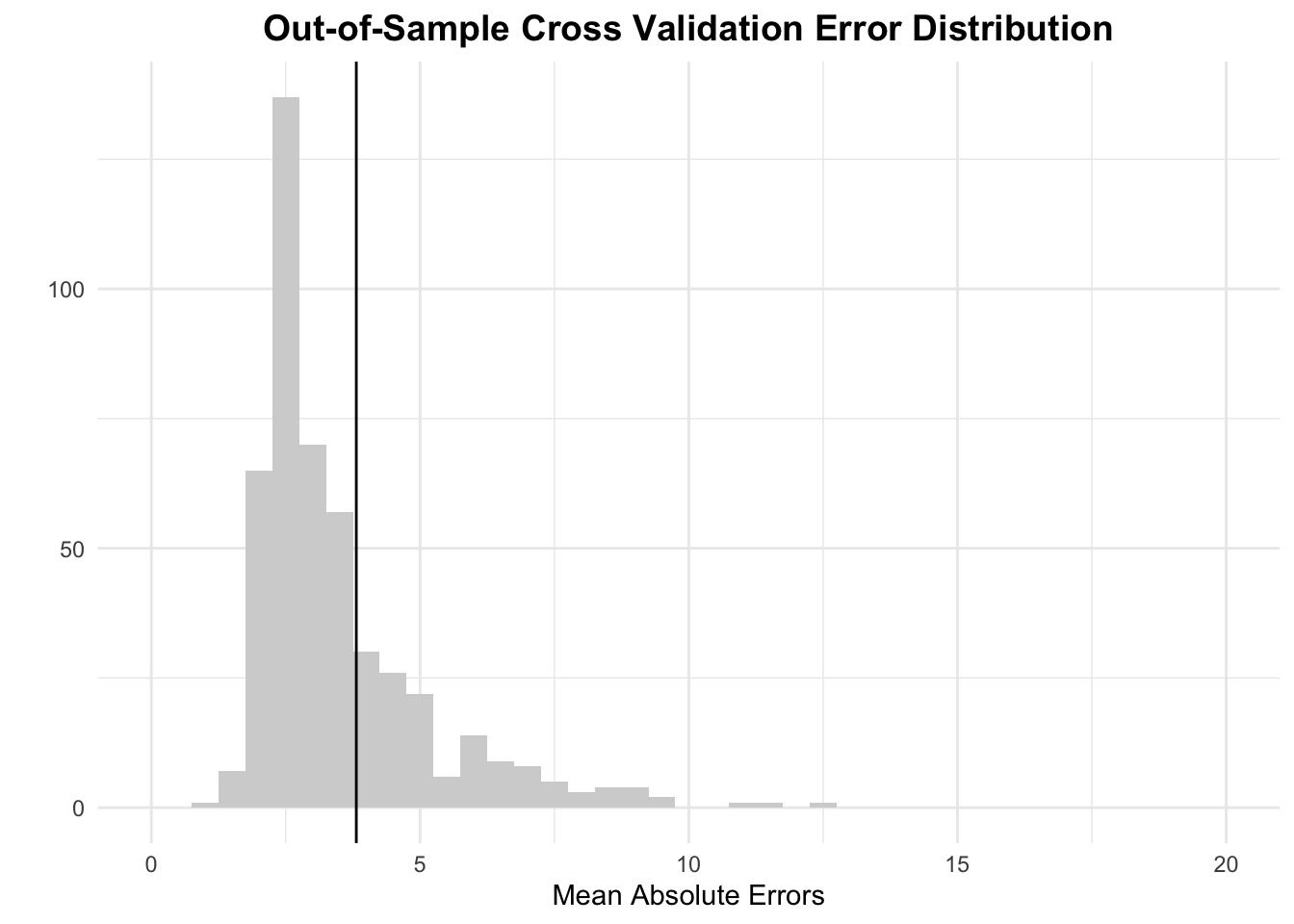

To understand my out-of-sample error, I performed 1,000 repetitions of random sampling, with each sample using 7 elections, which is slightly over half of the 13 total in the time frame of my data set. The average mean out-of-sample error, as shown by the black line in the graph below, is ~3.81%, a reasonably low number.

The above histogram shows the distribution of these mean errors. I have limited the x-axis of this graph to a reasonable range, so there are one or two outlier data points not shown above, though they are incorporated into the calculation of the average mean absolute error. I have restricted the x-axis so that we can better see that this graph is right-skewed. While there certainly are some outlier data points where my model failed to accurately predict the election, those are far outnumbered by instances of my model accurately capturing the state of the race.

Final National Two-Party Vote Prediction

Given this model, when we apply this result to the 2024 election between Vice President Harris and Former President Trump, we get the following prediction:

| Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 51.82711 | 46.55055 | 57.10367 |

As can be seen, my model predicts that Vice President Harris will win the national popular vote with 51.83% of the vote, a 3.66% margin over Former President Trump and his 48.17% share. There is still a relatively large range of possibilities considering today’s polarized political climate, with the upper bound of Harris’ vote share with a 95% confidence interval being 57.1% and the lower bound being 46.55%, meaning Harris could win by up to a 14.2% margin or lose by up to a 6.9% margin. Thus, to get an even better sense of the state of the race, it is important to now turn to the state level.

State-Level Model and Predictions

Equation and Variables

For my state-level analysis, I used two models, with both being OLS regression models built to predict what percentage of the state-level two-party popular vote the Democratic nominee should receive. The first is the primary model, and it uses the following six independent variables:

- October State-Level Polling Average: The average of state-level polls taken in October, as compiled by 538, and weighted by how many weeks were left until the election.

- September State-Level Polling Average: The average of national polls taken in September, as compiled by 538, and weighted by how many weeks were left until the election. For the roughly 3 states (none of which considered swing states) and 1 district (Maine’s 2nd) for which there were not any polls released in September but did have October polls, I set their September Polling Average to equal their October average so as to allow them to be included in the model.

- One Cycle Democratic Vote Lag: The Democratic candidate’s share of the two-party popular vote in the state in the presidential election immediately prior.

- Two Cycle Democratic Vote Lag: The Democratic candidate’s share of the two-party popular vote in the state in the presidential election two cycles (eight years) ago.

- Incumbent Party Status: Whether or not Democrats held the Presidency in the term leading up to the election.

- National October Polling Average: The average of national polls taken in October, as compiled by 538, and weighted by how many weeks were left until the election.

Taken together, the equation for my primary state-level model is:

$$ \mathbf{State\ Two\ Party\ Vote\ Share\ for\ the\ Democratic\ Nominee} = \mathbf{\beta_0} + \\ \mathbf{\beta_1} \textbf{ Oct.\ State\ Level\ Polling\ Avg.} + \mathbf{\beta_2} \textbf{ Sept.\ State\ Level\ Polling\ Avg.} + \\ \mathbf{\beta_3} \textbf{ One\ Cycle\ Dem.\ Vote\ Lag} + \mathbf{\beta_4} \textbf{ Two\ Cycle\ Dem.\ Vote\ Lag} + \mathbf{\beta_5} \textbf{ Inc.\ Party\ Status } + \\ \mathbf{\beta_6} \textbf{ Oct.\ National\ Polling\ Avg.} + \mathbf{\epsilon} $$Justification of Model

State-Level Polling: As you can see, there are a number of similarities between my national and state models. As previously explained, despite its flaws polling is still a strong indicator of results, and state-level polling is a good indicator historically of how that state will vote. For the same reasons as my national model, I included variables for both October and September averages.

Democratic Vote Lag: I added two new variables representing past election results in that state. While states certainly swing from year to year, most voters do not change their minds, so the last election, especially in today’s polarized political climate, tends to be a good indicator of future results. I included the two cycle lag variable for a slightly different reason. Including this variable bakes into my model how much the state shifted left or right going into the last election. While many states may only move slightly or may bounce around depending on the year, some other states (ie. Alaska, Texas, Massachusetts) have fairly consistently trended left in recent cycles, while others (ie. Arkansas, Nevada, Florida) have trended rightwards relative to the nation. These trends tend to be because of gradual demographic changes within these states (such as Texas’ rapid growth and diversification) or because of gradual realignments in the composition of the two parties’ political bases (such as Democrats’ gradual growth among high-education suburbanites). As such, I felt it important to add a second variable to include a measurement of these trends.

Incumbency: Here I have factored in incumbency slightly differently than in my national model. Since my national model was based around the incumbent party, it was important to test whether the candidate themselves were an incumbent running for reelection or not. Now that my model is based around Democratic vote share, I felt it was more important to focus on party incumbency more generally.

National Polling: Obviously this is a state-level model, but I wanted to factor in a variable for national polling averages, since in 2024 we find ourselves in an election where the national polling environment indicates a shift rightwards from 2020, but state-level polling largely has remained stable compared to last cycle’s results. Thus, I feel like it is important to test the effects of both since, although they overlap slightly, in tandem they may catch trends previously left unnoticed.

Unfortunately however, this model only can be applied to the relatively few states for which we have publicly available polling. There are many states that are considered to be safely in Democrats’ or Republicans’ aisles that no polling firms has decided to invest resources in polling for non-internal purposes. Thus, knowing that these safe states will not affect my electoral college prediction I decided to make a second, slightly simpler model for them. This supplementary OLS model drops the variables for October and September state-level polling averages, but it adds back in the national September polling average IV from my national model so as to replicate the potential September effects I explained above. In my primary state-level model, I decided that the inclusion of only the state-level September polling was sufficient and thus did not include the national September polling average in that primary model.

Regression Table

For my state-level models, I based them off of elections spanning 2000-2020. I chose to start at 2000 because I felt that this was the beginning of a relatively modern, slightly more calcified era of electoral politics. Furthermore, now that I have dropped Q2 GDP growth data from my state-level prediction, I can include 2020 data again without incorporating severe outlier data points like I would have in my national model. Thus, based off of the six above independent variables and the 290 state-level elections for which we have polling for presidential elections in this time frame, below is the regression table for my primary state-level model.

| State 2-Party Vote Share for Democrats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 7.51 | 5.07 | -2.47 – 17.50 | 0.140 |

| oct poll | 0.95 | 0.13 | 0.70 – 1.19 | <0.001 |

| sept poll | -0.18 | 0.11 | -0.40 – 0.05 | 0.118 |

| D pv2p lag1 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.26 – 0.50 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag2 | -0.01 | 0.05 | -0.10 – 0.08 | 0.835 |

| d incumbent | -0.95 | 0.52 | -1.98 – 0.08 | 0.070 |

| nat oct poll | -0.22 | 0.10 | -0.43 – -0.02 | 0.033 |

| Observations | 290 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.928 / 0.926 | |||

October State-Level Polling Average: For every 1-point increase in the Democratic candidate’s weighted October state-level polling average, we can expect an 0.95-point increase in their eventual state-level two-party vote share. With a p-value of <0.001, this is one of the three statistically significant IV’s in my primary state-level model at a 95% confidence interval.

September State-Level Polling Average: For every 1-point increase in the Democratic candidate’s weighted September state-level polling average, we can expect an 0.18-point decrease in their eventual state-level two-party vote share when controlling for other variables including the October polling average. This last point is important to note. With a p-value of 0.118, this is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval, but, like the September polling average in my national model that does not mean that the inclusion of this variable does not add value to my model.

One Cycle Democratic Vote Lag: For ever 1-point increase in Democratic share of the two-party popular vote in the state in the last election, we can expect a 0.38-point increase in the Democrat’s eventual state-level two-party vote share for the current year. With a p-value of <0.001, this is one of the three statistically significant IV’s in my primary state-level model at a 95% confidence interval.

Two Cycle Democratic Vote Lag: For ever 1-point increase in Democratic share of the two-party popular vote in the state in the election two cycles prior, we can expect an 0.01-point decrease in the Democrat’s eventual state-level two-party vote share for the current year. With a p-value of 0.835, this is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval. In fact, this variable has very little effect at all in my model, but I felt that it was important to include it both because I believe my reasoning is sound for doing so and because it plays a more important role in my supplementary model when my model will have to predict the trend of a state relative to the nation without being able to rely on state-level polling data like this primary model does.

Democratic Incumbency: For every 1% increase in “incumbency” there is an associated 0.95-point decrease in the Democratic party candidate’s state-level two-party vote share. Like with the incumbency variable in my national model, there is, of course, no such thing as a “1% increase in incumbency” as this is a binary variable. Nonetheless, it is still important to understand that incumbency tends to hurt Democrats in this model. With a p-value of 0.07, this too is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval, albeit narrowly so, but just like the September polling average and two cycle democratic vote lag, that does not mean it does not add value to my model.

October National Polling Average: For every 1-point increase in the Democratic candidate’s weighted October national polling average, we can expect an 0.22-point decrease in their eventual state-level two-party vote share. With a p-value of 0.033, this is one of the three statistically significant IV’s in my primary state-level model at a 95% confidence interval.

In terms of my supplementary model, below is the associated regression table:

| State 2-Party Vote Share for Democrats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | -30.82 | 5.88 | -42.41 – -19.24 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag1 | 1.09 | 0.05 | 0.99 – 1.20 | <0.001 |

| D pv2p lag2 | -0.11 | 0.06 | -0.22 – 0.01 | 0.062 |

| d incumbent | -1.83 | 0.59 | -3.00 – -0.66 | 0.002 |

| nat oct poll | 2.26 | 0.28 | 1.71 – 2.82 | <0.001 |

| nat sept poll | -1.63 | 0.23 | -2.08 – -1.18 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 255 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.935 / 0.934 | |||

I will not go into much detail at all about these numbers since this model is supplementary in nature, but it is important to note that four out of the five independent variables are statistically significant, and with the fifth, the two-cycle Democratic party vote share, being on the border of being so and being notably more impactful on the model’s outputs than it was in my primary model, indicating that it is serving its intended purpose of predicting longer-term trends.

Validation

For in-sample error, my primary state-level model’s R-squared value of 0.93 means that 93% of changes in state-level Democratic two-party popular vote share is explained by my model, representing a pretty strong correlation. This correlation holds strong when adjusted, with an adjusted R-squared value also of 0.93. These numbers are very similar for my supplementary model, with R-squared and adjusted R-squared values of 0.94 and 0.93 respectively.

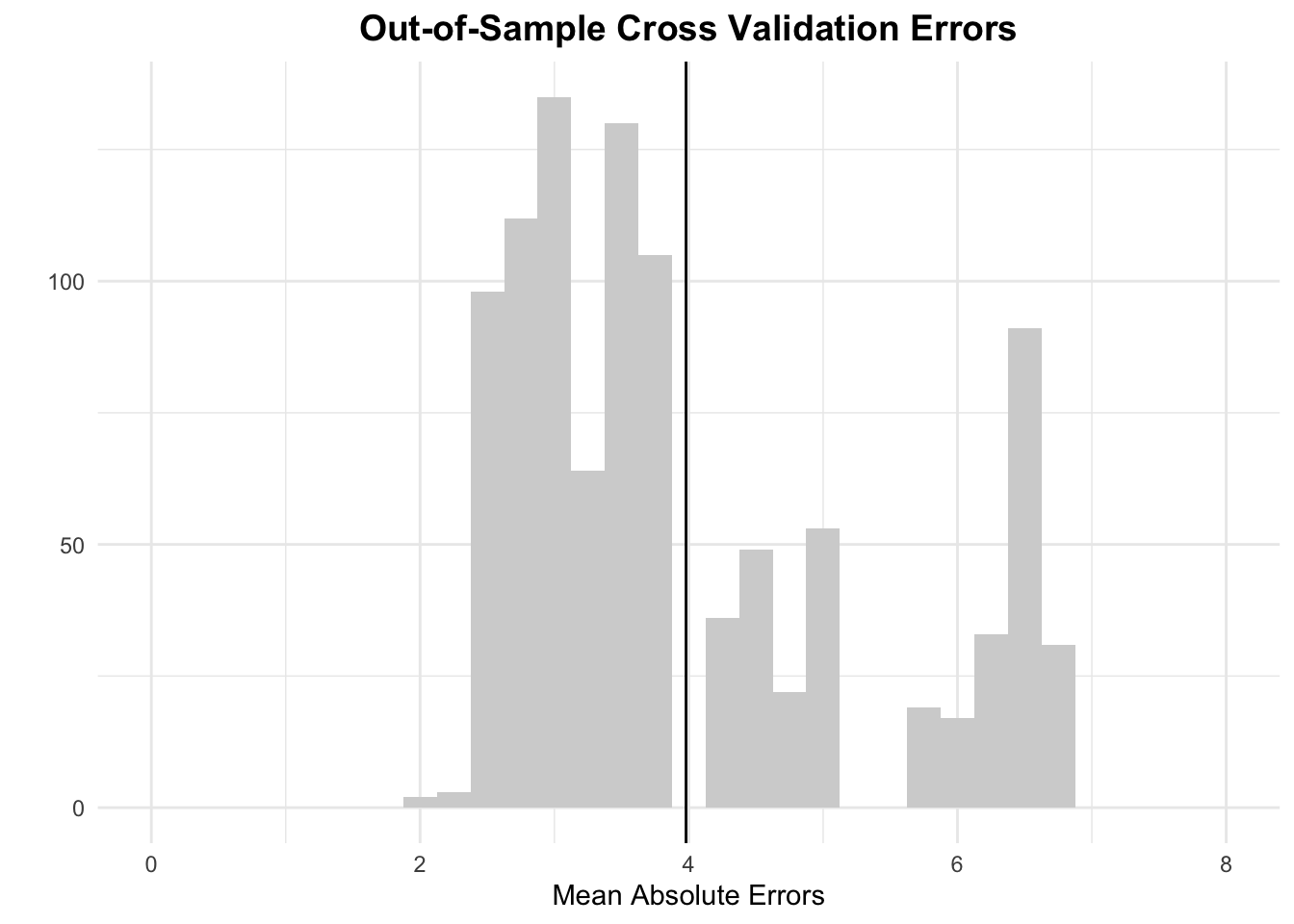

To understand my out-of-sample error in my primary state-level model, I performed 1,000 repetitions of random sampling, with each sample using 3 election years, which is half of the 6 total in the time frame of my data set. The average mean out-of-sample error, as shown by the black line in the graph below, is ~3.98%, a reasonably low number.

The above histogram shows the distribution of these mean errors, which is slightly right-skewed. While there certainly are some outlier data points that push above 5% where my model failed to accurately predict the election within a reasonable margin of error, most scenarios fall below that threshold, and there are no outlier data points where my model missed by an average of over 7 points. I will not bother repeating this out-of-sample validation for my supplementary model.

Final State-Level Two-Party Vote Prediction

Given the primary model, when we apply this result to the 2024 election between Vice President Harris and Former President Trump, we get the following predictions for states that have had publically available polling:

| State | Harris Vote Share | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 50.17068 | 44.85019 | 55.49117 |

| California | 65.17024 | 59.78080 | 70.55968 |

| Florida | 48.36540 | 43.03339 | 53.69742 |

| Georgia | 50.42399 | 45.10149 | 55.74650 |

| Indiana | 41.34649 | 36.02409 | 46.66890 |

| Maine Cd 2 | 46.58067 | 41.26204 | 51.89930 |

| Maryland | 68.04048 | 62.66586 | 73.41510 |

| Massachusetts | 66.76200 | 61.39923 | 72.12476 |

| Michigan | 51.44157 | 46.11853 | 56.76461 |

| Minnesota | 53.89702 | 48.57408 | 59.21996 |

| Missouri | 43.16617 | 37.83319 | 48.49915 |

| Montana | 41.09607 | 35.77414 | 46.41800 |

| Nebraska | 40.09414 | 34.76453 | 45.42374 |

| Nebraska Cd 2 | 54.57686 | 49.24191 | 59.91181 |

| Nevada | 51.36874 | 46.04218 | 56.69530 |

| New Hampshire | 54.67997 | 49.34864 | 60.01130 |

| New Mexico | 54.62405 | 49.29581 | 59.95228 |

| New York | 59.86333 | 54.49855 | 65.22812 |

| North Carolina | 50.31757 | 44.98784 | 55.64730 |

| Ohio | 46.02362 | 40.70049 | 51.34675 |

| Pennsylvania | 51.23316 | 45.90608 | 56.56025 |

| Texas | 47.12235 | 41.80247 | 52.44224 |

| Virginia | 54.64381 | 49.32428 | 59.96335 |

| Washington | 60.57076 | 55.22182 | 65.91970 |

| Wisconsin | 51.20178 | 45.86424 | 56.53932 |

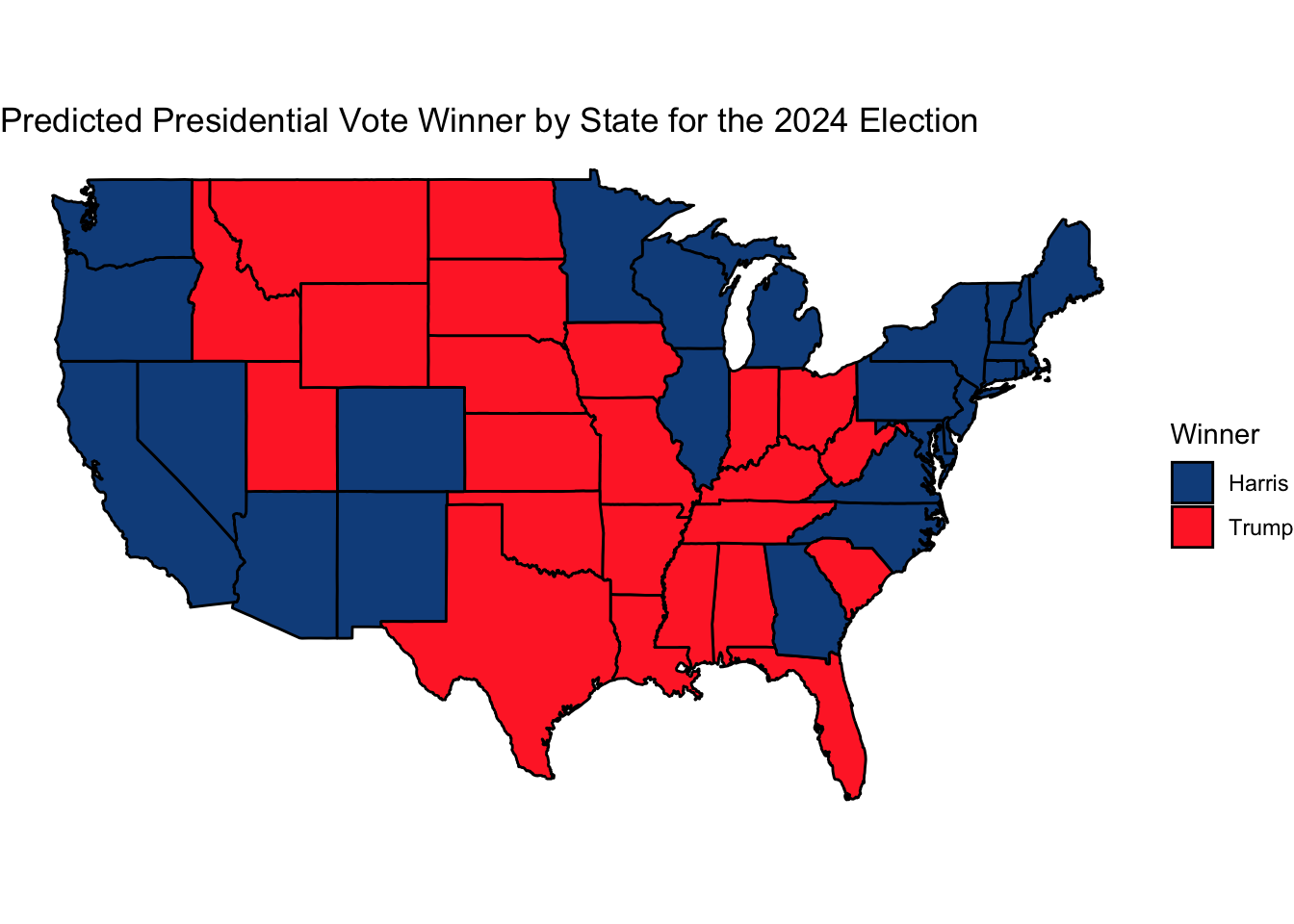

When you combine these results with my supplementary model’s predictions for states without polling data, you get the below map of my prediction for the nation, with states shaded by whether they will have voted for or against Harris:

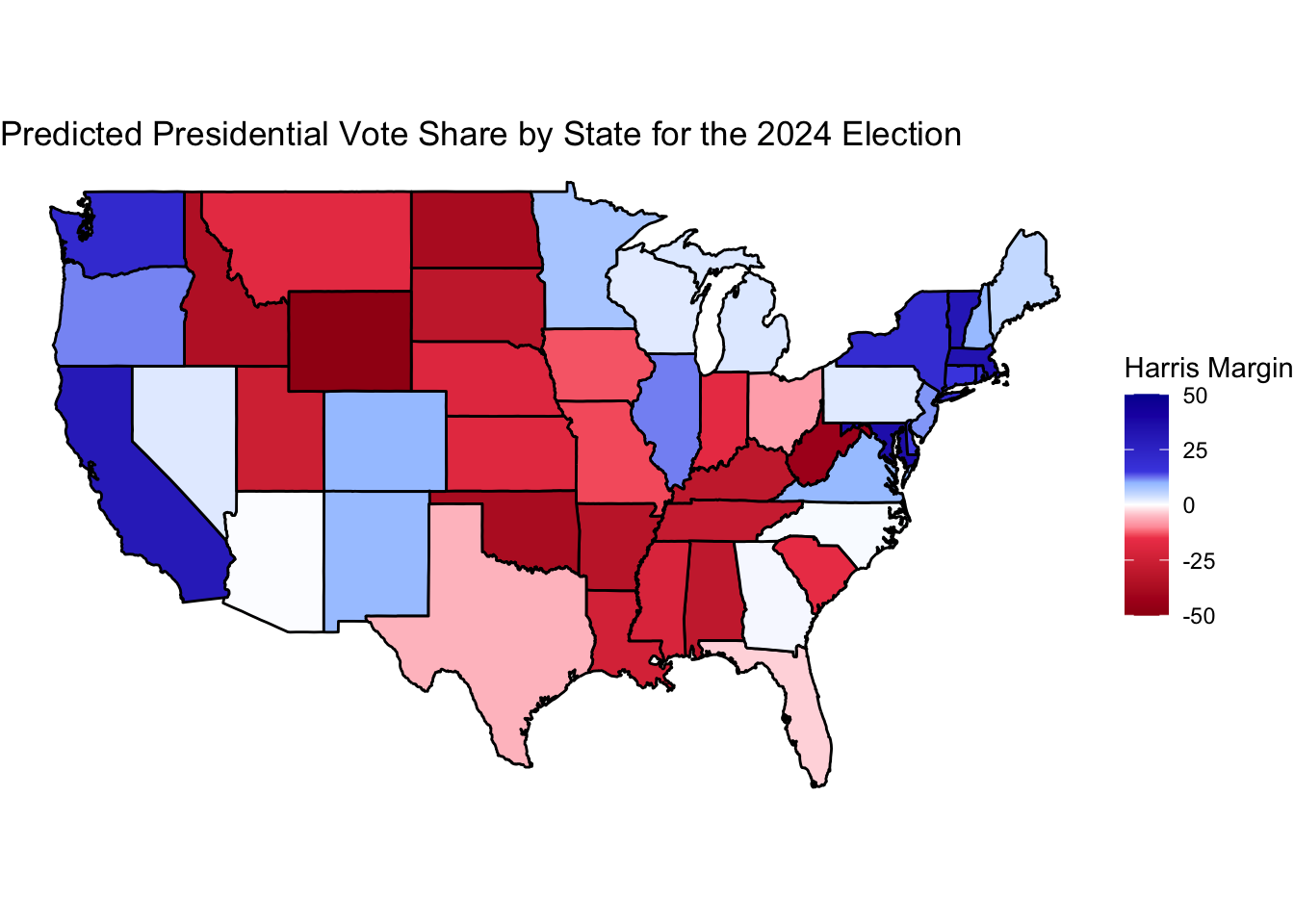

Not visualized here are Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District and Maine’s 2nd Congressional District, which go to Harris and Trump respectively, nor Trump-won Alaska or Harris-won Hawaii. Altogether, this map predicts a Harris victory in the electoral college 319-219 votes. Once again, however, this is a close election, and the table above with the predicted results for states with polling (which includes all key swing states/districts), shows that either party is easily within the confidence bounds of winning 270 electoral votes. The map below, which shows Harris and Trump’s predicted margins in states, helps visualize how close this election is in those key states.

Conclusion

Overall, if my models are correct Harris would narrowly win the crucial swing states and national popular vote, making her the first ever Madam President-Elect, but we will soon see whether we have to wait longer to utter those words.